It’s a brand new year, people. Four days in, and my brain is still rife with metaphors of new-fallen snow and fresh starts and resolute setting of goals.

But for all the rhetorical power of these conceptual flights of potentiality, I am stuck with the distinct feeling that the old year bloody well followed me home and sits lolling about on my desk, laughing at my attempts to clean slate and begin anew.

“Wherever you go, there you are,” an old friend used to say.

Where I am is still last year’s business. In fact, if 2012 really *was* the Year of the MOOC, I’ll be cozied up with last year for the next three months straight.

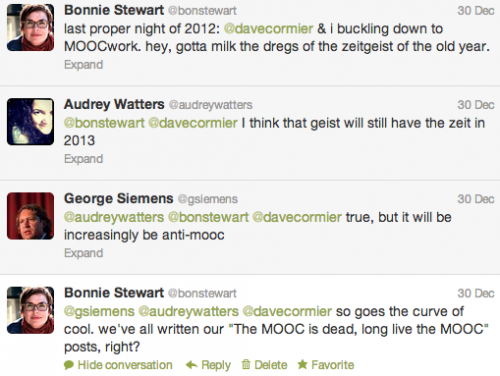

The night before New Year’s Eve, I joked on Twitter about Dave & I buckling down to work on the MOOCbook before the zeitgeist of the old year passed.

This morning I opened up my poor neglected blog and discovered the draft of this post, begun in July and last touched in late October, titled, in fact, “the MOOC is dead, long live the MOOC.” Apparently the joke is on me.

That’s the thing about MOOCs. They’re so everywhere that I can’t even keep track of what *I’ve* thought about them in the past couple of months, let alone the other copious buckets of ink spilled on the topic.

The whole damn thing has gotten so vast. And I feel as though it’s anathema to the current professional climate to ever admit one is overwhelmed, especially early in the new year, when one is supposed to be washed clean of all that baggage.

But there it is. Wherever you go, there you are.

***

Looking around at the broad higher ed/edtech scene, I suspect talking about MOOCs in productive ways is getting harder for everyone.

When there’s a clamour of voices, identifying the places and positions people are speaking from, let alone what’s left to be said, can be an assault from all directions. Trying to research MOOCs and write speculatively about what they may imply for higher ed is a lot like working in the midst of a big ol’ maelstrom. Mostly composed of verbiage.

Traditional models don’t suffice. Good research tends to try to be clear about which shoulders of giants it stands upon, and which gap in knowledge it aims to address. MOOCs are still such a moving target that the gaps in knowledge and direction aren’t really yet clear. And news reporting thrives on a heady mix of sensationalism and actual change, both of which are beginning to wear thin.

Because the biggest obstacle to effective conversation about MOOCs is that none of us IN the conversation – even the biggest names – appear to be clear yet on what MOOCs are or can be, or on where they begin and end.

As Dave put it in his inaugural appearance in ye olde fancy Wall Street Journal, “Nobody has any idea how it’s going to work.”

I’d go a step further, beyond the business model aspect of the conversation. I think the challenge with MOOCs, at this juncture, is that nobody has any idea what they are. This makes talking about what they *can be,* let alone their effects on what *is* in contemporary higher ed, rather a challenge.

Roger Whitson nailed it back in August after the first #MOOCMOOC experiment, with his Derridean claim of “il n’y a pas de hors-MOOC” or There is no-outside MOOC; there is nothing outside the MOOC.

We *know* what we mean when we talk about higher education, or at least, we believe we do. We have a broadly agreed-upon societal understanding of where the perimeters of that conversation lie. In fact, the perimeters of that conversation have traditionally lain more or less where MOOCs begin.

But where do MOOCs end? If we are talking about experimentation with learning online, on any kind of mass scale, are we then talking about MOOCs? How do we distinguish one possibility from another?

A year ago, MOOCs themselves were a rather small experimental niche; a loose but vibrant network of learning focused around principles of connectivism and openness and distributed, generative knowledge. Then Sebastian Thrun opened up the AI course at Stanford: to those for whom MOOCs were familiar, the term fit.

George Siemens called the AI course a MOOC back in August, 2011. The media gradually caught up, because there was no other equivalent term. When Thrun founded Udacity and the hype began to build, the word “MOOC” followed. And the rest, as they say, is history. Rather accidental history.

One of the most fascinating things about the proliferation of MOOC buzz is the way in which it’s made visible the networks by which media and higher ed make knowledge today.

But here we are, wherever we go. MOOCs mean video lectures. Or they mean distributed, aggregated means of making new knowledge. Or they mean democratization, or disruption, or whatever other Christ-on-the-cross people want to hang their futures on.

So how do we talk about the Internet happening to education without getting hopelessly mired in Wittgensteinian language-games? How do we begin to sort out and advocate for what we want MOOCs to be, when conversations about them tend to immediately point out that participants are speaking from entirely different reference points and hopes and belief systems?

I wish I knew. That’d be a heady way to start the new year. Instead, all I know is too much is being conflated under this bubble, as if everybody just woke up and noticed the internet might actually be relevant to higher ed. In that sense, I almost hope the 2012 narrative around MOOCs *is* good and dead, much as I doubt the calendar shift simply erased it.

But I also know that this messy, paralytic conversation remains one of the liveliest things I’ve ever participated in professionally, in almost twenty years in the field of education. The idealist in me says that if we don’t know where MOOCs end, then maybe their possibilities are still grandly open.

For me personally, the value of MOOCs has been primarily in belonging: in finding ways to connect and learn and share within otherwise too-broad networks. In that spirit, then, I’ve signed up for two new (connectivist-style) MOOCs this month – #etmooc and the second #MOOCMOOC – in the midst of the book-writing and thesis-researching on the subject. I’m hoping the more active engagement will help rejuvenate my own sense of the meta-conversation, and where to speak from.

Three short comments

– I think in identifying George’s article that called Thurn’s AI course a “MOOC” you have in fact named a key spot where the term stopped being meaningful (ironic, but if meaning is use, it can also be consistent “mis-use”)

– the phrase “without getting hopelessly mired in Wittgensteinian language-games” seems to me to exhibit a common misunderstanding of Wittgenstein (perhaps filtered through Lyotard’s reading?) I believe his point was exactly that there is NO getting outside language games, that the quest for some absolute denotative relationship was a fool’s errand

– that said, your post’s title seems exactly right, as does your conclusion. If we aren’t going to reify (which is exactly what we do with the attempt to define, once and for all, “MOOCs”) we must iterate, use and inhabit. It’s the same reason for me that the answer I love from the artists I respect most about “what is art?” is usually just a sympathetic shrug of the shoulders, a stubbing out of the cigarette, and them going right back to what they were doing.

Happy 2013, Scott

happy 2013 to you, too. thanks for the ideas.

i went on below about Wittgenstein – which you’re quite right, i still probably don’t understand – but am still thinking about point #1. i don’t know if mis-use is so easy to call out: i remember the Twitter conversation vividly when the announcement came out about Stanford…it was George who blogged about it, but i was one of the chorus of people enthusing “it’s a MOOC!”

and from what i could see then, it was. the scale wasn’t yet visible, nor the pedagogy, but Thrun was opening up registration to a free, online course. and my response was excitement…because i thought it meant that MOOCs as i understood them were catching on. i’d been teaching online since ’98 at this point and i’d seen a fairly steady progression away from the glorified correspondence course model that had been catchy when i started…it never occurred to me that giant MOOCs wouldn’t build on the open foundations of what i was familiar with. error of ego-centric thinking, but i think it’s fairly human to first assume, when one hangs out with ducks a lot, that other things that quack are ducks too?

anyhoo. all that not to defend the assumption but more to ask, is it a mistake only in hindsight? you must’ve been watching then too, in August 2011…what did you think? genuinely asking. :)

P.S. I also completely recognize the contradiction between my first point and my last two. I contain multitudes.

ha. don’t we all? perhaps that’s the problem with the openness of MOOC as signifier. or the marvel of it. god, i can’t decide. here we go again. ;)

i get what you’re saying about Wittgenstein and agree – to put it far too simply, naming goes against the multitudes within us and there’s no getting outside of it all to “proper” definitions – what i was trying to indicate was more that i don’t want to get mired in looking for those proper definitions but do want to be able to identify the threads of the conversations and the places we’re speaking from. my assumption is that new iterations will spawn new terms, but i think the possibilities and the paralysis both are in the wild openness of this one.

The only thing I can suggest is what I suggested in the last paragraph to my recent piece on “PLE Diagrams” (http://www.edtechpost.ca/wordpress/2012/12/19/ple-diagrams-observations/), that instead of using nouns we try to use verbs/gerunds to describe things which aren’t actually “things” but emergent phenomenon. I don’t know for certain that it does actually solve the problem, but in my own mind at least it seems a small amelioration to our constant tendency to reify.

wow. that post contains multitudes, indeed. thanks for directing me there.

When a term like EDUPUNK or MOOC fans out so quickly, I think it becomes (as you indicate) more a marker of the conversation we want to be part of than a description of a thing. The use of the term becomes an attempt to map the uncharted space, and everybody wants their piece of that territory mapped in the way it fits in.

Linguistic purists freak out about this. I think I got dinged by some people a while back when I said you can’t really “appropriate” the term EDUPUNK, because it’s *language*. It’s appropriated every day by its very nature. Others thought that somehow the term could remain pure and that would keep our actions pure. I disagree, since everything I know about linguistics tells me that words are often doing the most work when they get murky. Murkiness is a sign that you’re at the nexus of something big and valuable.

“MOOC” plops down right in the middle of our current problem space and says essentially that our current classes are SCFCs – Small, Closed, Face-to-Face Courses. How would flipping these elements on their head change things? What opportunities would it open up? What models could emerge?

That’s the reason I think (still think) it’s a brilliant term — because it doesn’t actually name a thing, it names an opportunity space, and that’s why the conversation around it, despite all the hipster-like naysaying, has generally been really productive. I may run around saying that “massive” is the overrated element of MOOC — but I can only do that because the term has supplied a shorthand map to the problem and opportunity space.

If you look at the smaller EDUPUNK wave you’ll see everybody complaining week three that they are *so* sick of EDUPUNK. Two years later you see everybody saying “Why is no one blogging anymore, remember the days of EDUPUNK when we were all blogging and talking about this stuff?” Life’s too short (and education to important) to get jaded I think. The MOOC blowback will be interesting as well, and will come no matter what, might as well enjoy it…

Mike…indeed. i think the blowback began awhile back, from the closest circles…as things usually go. like i said, i started – and titled – this post back in July. it’s kinda fascinating: we are all aware of the cycles of things and wary of hype and, in a sense, mass acceptance, especially any who work in experimental areas or within circles of cool – what Bourdieu would call restricted capital. and we form attachments to things in their early forms – attachments of identity and belonging – and these ties get blown open with mass acceptance, if not necessarily blown apart. i don’t know if the xMOOCs will actually disrupt higher ed, but they sure have disrupted the world of cMOOCs. yet i think the ties will…like you say…survive and remain visible once the cycle spins again.

i was never entirely an insider to the early MOOCs – i was on the periphery via Dave, but didn’t get involved in the research until 2010 – so less of my identity and effort have been invested in that iteration of the term. still, i do hope to see a shift towards recognition and inclusion of the principles of those early MOOCs in the newer, bigger versions. i know Downes has talked about this possibility (http://advanceducation.blogspot.ca/2012/11/when-is-mooc-not-mooc-what-mooc-means.html) and my brief foray into the world of Stanford’s AI lab last month suggested it’s not impossible.

whatever happens, yep, it’s interesting. :)

Arggh! My epic all-clarifying comment lost to the WordPress demons! Arghhh! It was so.. eloquent… insightful… full of cheese…

My reaction to comment when I saw your tweet was pretty much what you wrote here- we don;t even know what this MOOC thing is, it is becoming more elepant-ly diverse each time some article touches it.

I for one am a bit bored with talking about MOOCs and MOOCs about MOOCs. I want MOOCish experiences where things are done in an area, a subject. MOOCs deployed maybe.

However, it is important to me that people work this out. And I could not be more happy to know that Team Stewart + Cormier is on it.

Even mocking MOOCs is getting old. Well, I might not be able to resist a few more animated GIFs of silly cows.

it is so sad when WP eats all the cheese for itself.

your words are kind, Alan. thanks..and part of me wonders if my own overwhelmedness isn’t partly ennui. or at least desire to avoid these messy parts of the conversation and move on. but that would be too easy. i think there’s maybe still room for creativity here.

don’t stop posting cow GIFs, though. gawd. what would the world come to?

I like the idea of “MOOCish experiences where things are done in an area, a subject.” MOOCs have so far been offered mainly as “added value” from traditional institutions and tenure-track faculty members as “contained” courses via such new-fangled entities as EDx and Coursera. However, might there not also be ways for those of us without traditional academic appointments and possibly even unemployed! ;-) to participate in things MOOCish? I’ve been trying to figure out a way to do something in the area of music history & culture (across various genres and periods). I like the way Smarthistory (http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org) comprises a multimedia web-book on art history that can be used in any number of courses. Its creators told me that it’s mostly used by non-major undergraduates, but that lots of graduate students and faculty members also use it. With 5 million visitors, it’s also a massive, open, online … something!

i love the idea of “MOOCs deployed” too, Durrell. for years, we’ve actually thrown around the idea of doing a Dylan MOOC…having people just take areas of his life and work and leading discussions based on their own appreciation. never come to pass, but maybe someday!

That’s not what I mean, though. I want to develop a large-scale online learning environment about music history & culture (classical, jazz, world, folk, rock, pop, country, film, TV, electronic, etc.). It would include some content by me (and later probably by other scholars), but also discussion/linking/member-contribution capabilities for anyone to learn from and figure out which types of music matter to them, and HOW and WHY. It wouldn’t mainly be something for existing fans of one type or music, a specific composer or artist, or whatever. It’s hard to explain, because music academia has mostly been siloed away from broader cultural discussions for decades.

nah, i didn’t think the Dylan MOOC was necessarily at all what you meant, only that i think there’s a lot of room for rich MOOCwork in music, partly b/c so many people do have attachments to it.

you should definitely try to run the broad musicMOOC you envision…i can see real value in being able to trace literacies and tastes across the siloes. if it ever flies, please let me know. :)

I’m glad to hear you’re on board for another run at #MOOCMOOC, Bonnie. When we went in to revise the course, to update it and make it relevant again (since now everyone knows about MOOCs and what they are), we realized that most of the content points to questions people are still asking. While I feel similarly to @cogdog about the perpetual motion machine of these questions about MOOCs, I don’t think we can stop asking them yet because, well, we haven’t stopped asking them. Joss Whedon, when asked why he kept making shows with strong female leads, responded: “Because you keep asking that question.”

We may be tired, but as educators, don’t we make our fortunes on asking questions?

And, maybe that’s what MOOCs are about in the end. Something to get us riled up, to get us reconsidering education in general. Online learning LMS-style didn’t really do it for us. I know that Alan didn’t really like Jesse’s and my article, but I maintain that a MOOC is not a thing, it’s a strategy. And I wonder if, like so much of the Internet, the MOOC problem has risen from a kind of unintentional crowdsourcing, and has landed in our laps? Miscreant and petulant.

wait, Sean. we, as educators, are supposed to be making our fortune?!?

man, i keep doing things wrong. ;)

more seriously…i am energized by your prose and take on things, and the image of current MOOC problems as unintentional crowdsourcing, miscreant and petulant, both amuses and kinda inspires me, fooling me into believing we can just take MOOCs in hand and make of ’em what we will.

maybe it’s true. it was true in the beginning, but that was before they were a thing…or so far down the road to becoming a thing.

Cathy’s valid points today at #MLA about how the Xmodel MOOCs are essentially imperialist…and a fair amount of enthused uptake of that position from the Twitters…made me realize that the word is quickly not only becoming a thing but a thing that means almost the opposite of what it was originally intended to signify. yet these things we don’t like about MOOCs – i don’t like them either – aren’t inherent to the term. i’m not ready to foreclose on it! and so this strikes me as the time to try to collaborate and share and get that message out, while trying to encourage the Xmodels to change too. i dunno. hope springs eternal. or hope beats giving up? something like that. :)

mind you, none of those hopes have a business model. so maybe i’m just tilting at windmills.

Who said I did not like your article? Where did I say I did not like your article?

It’s just my middle school mentality way of poking it to see what its about.

I save my best lampoons for stuff I respect.

aw. there’s a lot of love in this room. :)

I’m sitting back and watching right now to see what it morphs into. I find it all fascinating.

likewise, Emily. it’s been a crazy, fast-moving, fascinating year, watching it all.

Pingback: Is MOOC reflecting how people learn? | Learner Weblog

I think the buzz about tying down MOOCs to a single and consistent definition is very similar to how it took considerable time after the fact for the Impressionism movement to be identified as such the Academy. At one point early on and after Monet titled a painting “Impressionism: A sunrise,” the radical reactionaires to classic realism had some kind of name to work with. “Hey you’re painting as an *impressionist* and that AI course, well it is a MOOC!” George Siemens is right, 2013 will be a backlash of anti-MOOC sentiment much in the same way that Impressionists vexed the entire art scene. In this blurb, how easy is it to substitute MOOc originators for Impressionists? “Because of the radical views of the Impressionists, in the time it was thought to be insulting to the existing art community. It took many years for Impressionism to accepted by the people and the art critics.“ http://library.thinkquest.org/C0111578/ieindex.html MOOcs are a natural result and collision of successful components of online learning, social media revolutionizing connections and networks, and a badly-needed response to CFCs. It’s the most radical undertaking yet of flipping the classroom, the ultimate flipping of CFCs – Small, Closed, Face-to-Face Courses and for profit online learning as well. I think MOOCs are also in part a generational thing: very few folks in their early 20s, college age kids, are clamoring for MOOCs. Certainly for me, MOOCs are a healthy response and yearning, a quasi nostalgia of lifelong learners who want to stay current and anchored in a formal yet low stakes experiential structure that mimics elements of CFCs. Advances in distant ed technologies (G+hangouts, youtube, Grant Potter’s ds106 radio, etc) have all made this wonderfully possible. I also see parallels between MOOCs and rap music. 30 years later, rap is still very much with us and shows no signs of going away soon. It took a long time for rap artists to be embraced by the mainstream. It began with very few lucrative props. It was DIY at its purest. Just a few rappers on the corner rhyming and making poetry of the neighborhood. Eventually and akin to ed tech startups, venture capital and the MITs and Stanfords having some luxury to set an expectation for everyone else that online learning isn’t going away, big money took an interest and eventually mainstream labels started signing rap artists. Rap and hiphop spun in different ways, analagous to xMoocs.

Ben, this fascinates me because on the plane ride down to California last month i was reading Bourdieu on the fields of cultural production, b/c i’ve long been trying to unpack the different forms of capital circulating in networked exchanges as part of my thesis. AND then, towards the end of the book, Bourdieu launches into a very detailed description of how Manet – and Monet – essentially forced open the terms by which the French art establishment determined what art was…and it occurred to me as i was reading that this little analogy fit even better with the MOOC part of my dissertation than with the broad social network practices part. so you have, in effect, confirmed my bias. ;) but yes…it’s all kinda fascinating, as is the rap layer you add. thanks for the comment.

Well, how about that? Remember that Police song, “Synchnonicity?” :-) I’ve not familiar with Bordieu’s work but as a 2013 personal challenge, I will read his text AND in French! Salut!

Oops. I meant to type: Synchronicity as in synchronous, synchronized learning. Here’s the link to the song: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMBufJmTTSA

Fascinating. And that Wall Street journal article which mentions Dave helped me understand some of the issues in layman’s terms.

the “there’s no business model” issue? yeh, i’ve been struggling over that one since February, when i first heard of Udacity.

to me, all the things that *can* be monetized in higher ed – without gutting the spirit of education and scholarship being valuable in and of themselves – already *have* been monetized. and so i struggle with what’s left for the startups to work with. yet, hey, people gotta eat so not all MOOC-work can be labour-of-love free. i keep hoping there’s a sponsorship model that may be more…to my tastes. ;)

Pingback: Mes intentions de communication à Villard de Lans | Mario tout de go

Pingback: The MOOC is Dead, Long Live the MOOC | theory.cribchronicles.com | momeNTUm