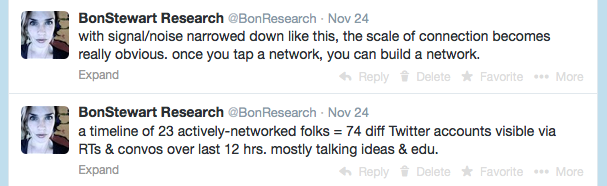

So. Since last November, I’ve been researching how networked scholars ‘read’ each others’ credibility and influence, when they encounter each other and each other’s work outside of the formal system of academia. I’ve been curious about the patterns running through the logics by which we make sense of each other; curious about what counts as influence in open networks. In a post a few months back I wrote:

“Influence is a complex, messy, slightly socially-discomfiting catch-all equation for how people determine the reputation and credibility and essentially the status of a scholar. There are two ways influence tends to get assessed, in scholarship: there’s the teensy little group of people who actually understand what your work really means…and then there’s everybody else, from different fields, who piece together the picture from external signals: what journals you publish in, what school you went to, your citation count, your h-index, your last grant. It’s credibility math, gatekeeping math. It’s founded in names and organizations people recognize and trust, with a running caveat of Your Mileage May Vary.

And now, in the mix, there’s Twitter. And blogs.

How can something that the general population is convinced is about what people had for lunch be a factor in changing what counts as academic influence?“

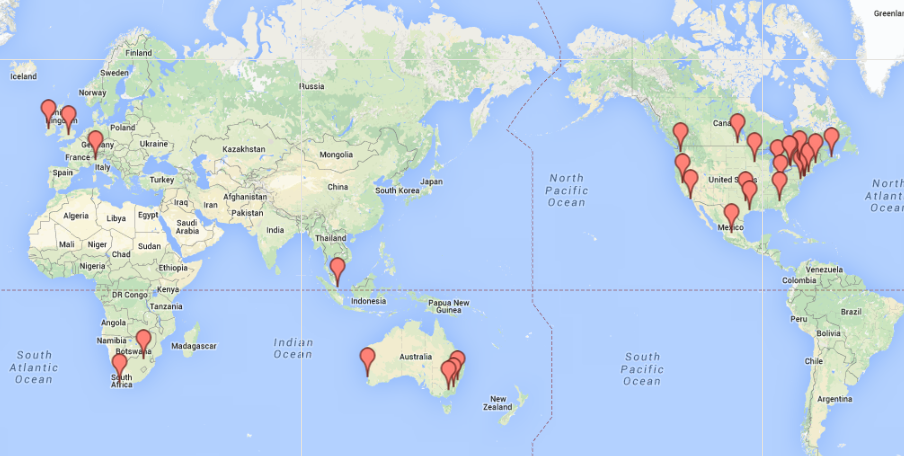

Well, here’s how. For real, with details and the permission of participants, the first run of findings from my ethnographic dissertation study of 13 actively networked scholars from various English-speaking parts of the globe. This is an excerpt from a larger paper currently under review…but this is the part I wanted open and out, now. “Findings” seems like such a funny word, suggesting this stuff was all laying out in the open to be stumbled over. In a sense, it is, always, every day, even on the days academic Twitter feels like crossfire. Yet it is also constructed, and situated, and ever-shifting. Feel free to post your caveats in the comments section.

WOOT. Onward.

***

WHAT COUNTS?

The central theme that ran through participant data was that scholars do employ complex logics of influence which guide their perceptions of open networked behaviours, and by which they assess peers and unknown entities within scholarly networked publics. More specifically, all scholars interviewed articulated concepts of network influence that departed significantly from the codified terms of peer review publication and academic hiring hierarchies on which conventional academic influence is judged.

While these concepts diverged, and I’ve attempted to be responsible to those divergences and diffraction patterns by sharing some breadth of the “history of interaction, interference, reinforcement, and difference” (Haraway, 1998, p. 273) within the space available here, they nonetheless suggest webs of significance specific to open networks. These webs of significance are, of course, situated knowledges, related to the stated and enacted purposes for which specific, variously-embodied participants engaged in open networks and the value they reported finding in them. Yet a number of patterns or logics emerged vividly from the data, in spite of the fact that participants had little in common in terms of geopolitical location or academic status positions. This suggests that alternative concepts of academic influence circulate and are reinforced by the operations of open, scholarly networked publics, particularly via Twitter.

It is important to note that participants’ stated reasons for engaging in open scholarly networks generally exceeded the instrumental “this will increase your dissemination and citation count” impact narrative. This may be in part because the study required that all participants had been active Twitter users for at least two years prior to the beginning of the study in November 2013: a review of higher education publications suggests the strategic narrative did not become prominent until after 2011. In any case, participant observation suggested that while some participants did primarily use Twitter in particular for broadcasting their own and others’ work, all participants in the study appeared to be engaged in curating and contributing resources to a broader “conversation” in their field or area of interest rather than merely promoting themselves or their work.

Among the 10 participants interviewed and the 12 who completed the profile assessments of other scholars (9 did both), there was consistent indication of an individual logic of purpose and value served by networked participation. In cases where participants reflected on their own changing practices over time, I observed a pattern indicating that an emergent sense of their own capacity to contribute to this broader conversation was part of the value participants attributed to networks. Particularly for those marginalized within increasingly rationalized institutions, and for those for whom the academic “role” does not cohere with a full sense of identity, reciprocal networked engagement can be a powerful way to extend beyond institutionally-sanctioned terms of circulation and value. In relation to the influence of others within open networks, participant responses suggested that they were able to perceive and ‘read’ influence outside their own areas of interest or the corners of the ‘conversation’ they perceived themselves contributing to, but were unlikely to follow people whom they perceived as disconnected from that particular part of the conversation, regardless of the apparent influence of those others.

Below are key emergent elements in these webs of significance, outlining what appears to count as a network version of academic influence in open scholarly networked publics. While both participants and exemplars gave permission for me to identify them by Twitter handle in all research publications resulting from the study, I have anonymized specific quotes from participants in relation to exemplars and identifiable others.

“She sure has a following” – Metrics matter, but not that much

A primary finding of the research was that metrics –the visible numbers attached to social media profiles and blogs – are seldom taken up in isolation. Participants showed a nuanced and relatively consistent understanding of metrics: the higher the number of tweets, the longer a profile was assumed to have been active, and the higher the ratio of followers to following (Twitter does not require reciprocal ‘friending’ in the way Facebook does), the more likely the person was to be perceived as influential. Yet equally consistent across the data were caveats of context, in which participants made clear they seldom interpret the metrics of public Twitter profiles as a final indicator of a scholar’s influence or potential value to their own network.

@socworkpodcast: “Status does play into my decisions to follow someone, if I see someone with a huge following, whose bio suggests this is a thought leader or a person of influence online/offline. I will look through the feed to see if the most recent 100+ tweets seem like things I could benefit from professionally, or that my followers might value.”

@antoesp: “I find it intriguing to discover how we all are able to provide a defined aspect of our multiple self through the micro-portrait in the personal twitter account. Usually I don’t choose to follow someone only on the basis of this micro-portrait, but I follow the link to his/her blog/SN profile (if provided).”

Most participants reported scrolling through tweetstreams and looking at blog links before making decisions about following: a few noted that profiles without links to external sites “for ideas in more than 140 characters” are profiles they generally avoid following.

The exemplar profiles with the largest number of followers and ratios indicating a high scale of attention did tend to be assessed as more influential. High tweet numbers indicate longevity on Twitter and appeared to factor into many participants’ assessments of others: some noted they were more likely to invest in following an established profile with many tweets because they could assume ongoing contribution rather than an account that might go dormant. This was particularly true among participants who appear to maintain a cap on the numbers of users they follow: this may indicate impression management regarding their own follower/following ratios, as well as efforts at signal/noise control. However, low tweet counts or relatively even follower/following ratios did not necessarily result in dismissal of influence: it was noted by participants that accounts with smaller followings can simply reflect relative newness within the Twittersphere. One participant noted, of small accounts, “Might just mean they haven’t done anything ‘viral’ yet. But I’m more concerned with content and interests.” Profiles that had not been adapted or personalized at all, though, were commonly interpreted as signaling a lack of value.

@miken_bu: “I check their twitter profile, read some recent tweets and perhaps check out their blog or web site… I do try to follow folks who have differing views or from differing backgrounds to reduce the echo chamber. I rarely follow anyone who has an egg image and no profile info, though, unless I know them already.”

@katemfd: “Sometimes…I’ll choose someone with twenty followers, because I come across something they’ve managed to say in 140 characters and I think… “oh, look at you crafting on a grain of rice.”

In terms of how participants amplify other voices in their own Twitter timelines, however, metrics appear to count to some extent. During participant observation, the majority of participants were more likely to re-tweet (RT) users whose scale of followers was higher than their own. Even where participants clearly made themselves available to engaging in discussions with users of all stripes and sizes, the tendency to amplify larger voices was consistent among all but the largest accounts in the study.

“A rolling stone gathering moss”- Identity at scale

While size or scale of account was not taken up as a direct indicator of influence or value, there did appear to be a critical mass at which those who are visible in open networks to become ever more visible. A number of interviews – with participants of varying scale – noted that for large accounts identity and reputation can become “a thing,” and the reciprocal communications upon which many participants build their networks becomes difficult to sustain.

@catherinecronin: “Large nodes in a social network have more visibility, their network activity gets amplified, and they become larger yet. In Twitter this happens in many ways – through RTs, through publication of “top educators to follow” lists, etc.”

@wishcrys: “I think when someone is a Twitter personality with a Twitter reputation, regardless of their content people are just going to like it – reputation comes to overshadow content. At that point you’re no longer a content producer, you’re probably just a Twitter personality…everything you say is Gospel Truth. Whereas when you’re lower down and trying to gain some form of connection, recognition, some sort of following, your archive and content are what leaves a mark.”

Participants who had reached significant scale with their own Twitter accounts, blogs, and digital identities tended not to speak about size of account as a benefit or goal, but more as an identity shift; one that involves challenges, adjustments, and responsibilities, as well as privileges.

@raulpacheco: “(January 2014) –I find when I have conversations on academic Twitter my brain starts absorbing information on data and learning, new ways of looking at things. I’m addicted to my mentions tab – I love hearing people react to what I say.” (July 2014: Skype chat) – “I’ve reached peak tweetage. I can’t answer every single @ reply as I used to (related to how much my follower count has grown).”

@readywriting: “I make sure that I amplify a lot of adjunct voices now. I think that’s really important. POC, other marginalized people…I recognize my privilege and want to use it for some good, even if it is just amplification.”

“Status baubles” – The intersection of network influence with academic prestige

The intersection of high network status with lower or unclear institutional academic status was a recurring topic in interviews, in reflections, and in public Twitter conversations. Participants indicated that the opportunities sometimes afforded junior scholars with network influence can create confusion and even discord within the highly-codified prestige arena of academia, because the hallmarks of network influence can’t be ‘read’ on institutional terms. Networked scholars were acutely aware both of network and academic terms of influence and appeared to codeswitch between the two even on Twitter and in other network environments. However, they noted that colleagues and supervisors tended to treat networked engagement as illegitimate and, in some cases, a signal of “not knowing your place.” Of the alternate prestige economies that intersect with academia, participants reported media exposure as the most coherent to their less-networked academic peers.

@tressiemcphd: “It’s the New York Times and the Chronicle of Higher Ed…I get emails from my Dean when that happens, when I show up there. With the Times I get more from the broader discipline, like a sociologist from a small public school in Minnesota – people not so much in the mix prestige-wise, but they see someone thinking like them, they reach out. But the Chronicle gets me the institutional stuff: I’ve got a talk coming up at Duke, and the person who invited me mentioned that Chronicle article three times. It’s a form of legitimacy. It shows up in their office and so they think it’s important.”

@thesiswhisperer: “I’ve grown this global network sitting on my ass and it offends people. And I’m really interested in that, in what’s going on psychologically with that, they say “it’s not scholarly” but it’s really just not on their terms. It has success. But when you’re the one getting keynotes people who’ve bought into older notions of success, they feel cheated.”

“I value their work, so value by association” – Commonality as credibility and value

When it came to indicating whether they would personally follow a given account, participants appeared to give less weight to metrics and perceived influence than to shared interests and perceived shared purpose.Most participants appeared to be actively attempting to avoid what Pariser (2011) calls a ‘filter bubble’ in their networks. Rather, many reported seeing themselves as responsible to their own networks for some level of consistent and credible contribution, and so sought to follow people who would enrich their participation via relevant resources or common discussion topics.

Where commonality appeared even more important to participants, however, was in peers or shared networks: when a logged-in Twitter user clicks on another user’s profile, the number and names of followers they have in common is visible. This visibility serves to deploy shared networks as a signal of credibility in an environment where identity claims are seldom verifiable. Many participants spoke to the importance of shared peers over metrics or other influence factors in terms of whether they choose to follow. In assessing a full professor with more than 1,300 followers, one participant noted that the metrics did not sway him: “Looking at the number of followers and tweets, it would seem as if this person has some ‘gravitas’ in the field. Just judging from his profile – I would not be particularly drawn to following him because his field is chemistry. I searched his profile online, and looked at his tweets, and he tweets mostly about non-academic issues e.g., coffee, football, etc.” Whereas the same participant then indicated he would follow another profile with only 314 followers, due to shared networks: “she is followed by a number of people whom I respect and follow. So I will give her a try.”

Participants tended to look for common interests on top of common peer networks, however. One mentioned, “I often follow people who others I follow also value – after ‘checking them out’ via looking at some tweets, profile, etc.” Another echoed, “I see that we share 65+ followers, so there are obviously many connections. (Her) interests match mine somewhat, she shares resources as well as engaging with many people…I also see that…(her) use of these particular hashtags tells me that (her) interests are closely linked with mine.”

Commonality was also overtly valued where participants used networks as ways of connecting with other scholars for support, encouragement, and specialized information: this was common both among PhD students and early career scholars in the study, as well as among those who use open networks for ongoing learning. One PhD candidate reflected on the value of another PhD student account, “As a PhD student, she is a colleague studying topics close to my interest. I am likely to follow her for a sort of…solidarity among peers, beyond the actual contribution she could bring.”

“Being connected with Oxford adds to the reputation” – Recognizability as a way of making sense of signals

The value placed on shared peers reflects a broader pattern observed within the research: recognizable signals have a powerful impact on perceived influence and perceived credibility. In the same way that recognizable journal titles or schools or supervisors serve as signals of conventional academic influence, so do both conventional and network factors of recognizability carry weight in assessments of network influence. Thus, shared peer networks matter, as do visible acknowledgements such as mentions and retweets; additionally, familiar academic prestige structures such as rank and institution can add to impressions even of network influence.

One of the most vivid examples of this was the workplace listed on one exemplar’s profile: Oxford University. The vast majority of participants who were shown this exemplar noted the Oxford name, and there was an overwhelming tendency to rate the account as influential. However, as previously noted, influence did not carry as much weight as commonality when participants were asked to weigh whether they’d follow a user: one participant reflected, “Is based at the University of Oxford – signaling for me a possible gravitas/expertise in the field. Looking at his tweets, he does not tweet a lot about academic issues – so he is most probably not, in my opinion, a very ‘useful’ person in my network.”

The Oxford exemplar also raised the issue of reciprocality and the ways in which its likelihood is minimized by scale of metrics and by prestige. One participant was frank: “This person seems like a very successful academic and is doing forward-thinking work at one of the oldest and most prestigious institutions in the world…(but) I have not followed him and couldn’t imagine he’d follow me.” Another was more overt about the ways in which influence is generally understood to affect engagement: “Clearly a more discerning twitter denizen (note the number of people following him vs who he follows), which would tell me he might not be big on interaction.” Thus, imbalance of scale does not necessarily fit with the purposes of connection and tie-building that many scholars turn to their networks for.

Outside the Oxford example, institutional affiliations or lack thereof did not have much effect on participants’ responses to exemplars, presumably because few institutions in the world carry the recognizability and prestige that Oxford does. Still, institutional affiliations can operate as credibility signals even where prestige structures are not involved.

@exhaust_fumes: “I care a bit about institutional affiliation in profiles…less that the actual university matters or rank matters, but that people are willing to put any institutional info up makes me more inclined to follow because I find relative safety in people who are clearly on Twitter as themselves as academic-y types and therefore aren’t likely to be jerks without outing themselves as jerks who work in specific places.”

Willingness to openly signal one’s workplace can operate not only as a verifiability factor but as a promise of good behavior of sorts. However, signals of institutional academic influence were also read as indicators of identity and priority: in reference to a profile that opened with the word “Professor,” one participant commented, “When a profile leads with institutional affiliation, I assume that is his primary role on social media. The rest of the cutesy stuff is there to humanize but he is signaling who and what he is in the traditional power structure.” Scholars who emphasize their conventional academic influence signals may limit the level of network – or “born digital” influence they are perceived to wield.

“A human who is a really boring bot” – Automated signals indicate low influence, especially in the absence of other signals

One clear indicator of a lack of network influence was automated engagement. Three exemplar identities had automated paper.li or Storify notifications in the screen-captured timelines that were shared with participants; one exemplar’s visible tweets were all paper.li links, or automated daily collections of links. Responses to the paper.li were universally negative, even where the exemplar was otherwise deemed of interest. “Potential value to my network – she tweets relevant stuff so probably I should follow her! On second thought, she has a Paper.li, and by definition I unfollow anyone who uses that tool.” Other participants were equally direct: “The only negative for me was the link to a daily paper.li. I tend to find those annoying (almost never click them!)”

Storify was not interpreted to indicate the same level of low influence or awareness, but its automated tag feature was still a flag that participants mentioned: “This is on the fence for me since Storify takes some effort to be engaged with things and maybe she didn’t get that she can opt out of those tweets informing people that they’ve been “quoted.”

“My digital networks provide me with some sense of being someone who can contribute” – Identity positions and power relations

Participants’ nuanced sense of influence in networks was particularly visible when aspects of marginality and power were explored. While none perpetuated the narrative of open participation as truly or fully democratic, many did note that networks have created opportunities and access to influence in different ways than their embodied or academic lives otherwise have afforded.

@raulpacheco: “In a very bizarre way, having a well-established academic and online reputation makes me feel pretty powerful, despite being queer and Latino…both elements which should make me feel handicapped. My thoughts are well received, generally, and my stuff gets retweeted frequently.”

@katefmfd: “Networking online has enabled me to create a sustaining sense of my identity as a person, in which my employment in a university plays a part, but isn’t the defining thing…my networked practice is much more closely aligned to my personal values, and much more completely achieved.”

@14prinsp: “My identity intersects with a particular (South African) view of masculinity and patriarchy – there’s vulnerability here. I’m out as a scholar, and I’m also HIV positive and am out in my department…I was very sensitive when I started blogging that if I said something stupid it would be there til death do us part, but I’m very aware that I manage my identity, I make very critical choices. It’s reputation management, it’s brand management, not in a superficial way: there is definitely some authenticity in it but it is carefully chosen.”

Particularly among PhD students and early career scholars, the norms of open online participation helped minimize academia’s hierarchies for participants.

@andreazellner: “I feel like Twitter is the Great Equalizer. Take a recent back and forth with the Dean my college…I am too intimidated to talk to him and he has no idea who I am, and yet on Twitter he posted about being at Microsoft Research and I started asking him questions. He ended up tweeting pictures of things I was asking about, etc., and we even traded a few jokes.”

@tressiemcphd: “My position in the prestige structure didn’t always match my ambitions and what I felt I could do, felt compelled to do. (Networks) allowed me to exist without permission: I was never going to get institutional permission, there was no space there.”

@wishcrys: “I’m far more likely to tweet to my academic superheroes or superiors: I’m not very likely to walk up to them and go “hey, great book!” I definitely feel much more comfortable doing this on social media…people aren’t going to remember my research five years down the road but they may remember that nice PhD student who sent out a nice tweet at 3am.”

Finally, it was noted that the relational connections created in open networks nonetheless reproduce many of the power relations of institutions and society, even while challenging some of their hierarchies. Networks were reflected as an alternate status or influence structure that intersects with academia, rather than as truly open fields of democratic interaction.

@readywriting: “I’ve consciously worked to follow people outside the class/race/gender norm: one of the evaluative things I do when I encounter a new person on Twitter is ask myself “is this person a little outside of the norm? Great. I want to learn from him/her.”

@catherinecronin: “Twitter is ‘flatter’ than some other networks/media, but power relations exist on Twitter — there is no doubt about that. The online very often reproduces and amplifies what occurs offline. However, open online platforms can also subvert the usual power dynamics. Those without access to conventional public communication channels can use social media to build networks and influence outside of institutional and cultural power structures.”

***

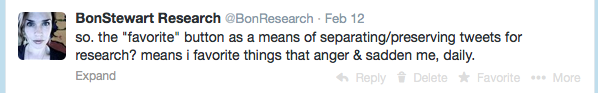

So that’s a start. There’s so much more data that I’m beginning to realize I’ll never do it all justice, the rich conversations, the mountains of Twitter favourites, the backchannels, all these signals that constitute a body of research just as they constitute the water many of us swim in, as networked scholars. My next paper will take this on from a literacies perspective, rather than strictly from an influence perspective. I keep learning.