So. I stood up in front of a whole room of academics and theorists and grad students with funky glasses this weekend and said the word “MOOC.” And nobody threw a single tomato, which surprised me.

My presentation for Theorizing the Web 13 at CUNY was entitled “MOOCs are Not the Enemy: Networked, Non-Imperialist MOOC models.” Or in simplest terms, “cMOOC is for cyborg.” Ahem.

The Cliff Notes version:

My base premises are these: privatization is bad and colonialism is bad and globalization is as shady as it’s always been and there are lots of totalizing systems at work in higher ed these days, old and new. But talking about these things through the lens of MOOCs increasingly seems to devolve into binary arguments against one totality while half-defending another, until it feels like the proverb about the seven old blind men and the elephant. A MOOC is a snake! cries the one holding the tail. No! It’s a sail! shouts the one with the ear in hand.

More Than is Dreamt of In Your Philosophy, Horatio

Both the elephant and the MOOC defy simple metaphors, because they’re huge. MOOCs make visible the intersection of a snarl of complicated axes of change and power relations in higher ed, so reifying them into a single axis – even if it’s the dominant one – leaves too much of the picture out. A MOOC is a course that is massive and open and online in some way and beyond that, for the moment, I’m agnostic.

Not because I’m not aligned: I am aligned. But because I think the conversation is too important to foreclose. There are a host of valid criticisms of MOOCs of all kinds, even the ones I really enjoy, and I want to be having those conversations and talking about the forces driving different MOOC models and driving change in higher ed. A lot of these forces scare the shit out of me, for the record. But I think – as I’ve heard other people say (I’d thought it was Cathy Davidson but I can’t seem to find a link) – that MOOCs are a symptom of these forces rather than the problem in and of themselves.

So dismissing MOOCs outright, or insisting on talking about all MOOCs as if they were one hegemonic thing rather than a still new and shifting collection of phenomena, shuts down the possibility of doing something more with them.

It gives the conversation over. I’m not ready to do that. I don’t want to give over – yet, at least – to the idea that anything about MOOCs is inevitable.

Beyond the Borg Complex

To be sure, we can’t be in higher ed today without being to some extent subject to the changes being wrought by privatization and globalization and the undermining of the narrative of public ed and the public good. These logics constrain budgets, shape policy, affect how what we do is taken up and the roles available to us.

The most dominant MOOC models embody a lot of these forces and logics. So they inspire vitriolic response: we don’t want to be the kind of subjects they seem to impose on us.

Or some of us don’t. In the ongoing Shirky/Bady back & forth about which end of the elephant is more equal than others, Bady pegs Shirky’s “it’s happening anyway, might as well adapt” response as a form of what Sacasas calls the Borg Complex, a determinist “resistance is futile” fatalism combined with a neoliberal identity approach.

But that conversation is still a binary. And leaves Bady to some extent defending the traditions of that other totalizing system, the conventional patriarchal and elitist mythology of “schooling” that many open online educational efforts exist to challenge.

I end up nodding hopelessly at the beautiful prose of the both of them and thinking about narrative escalation in pre-World War I Europe. With all this grandiose buildup, the Triple MOOC Entente and the Triple MOOC Alliance carve out increasingly opposed territories until I wonder if Archduke Ferdinand’s been shot yet and the bloody inevitability can just start, already.

Or we could explore MOOCs from a cyborg perspective.

A cyborg is not Borg

The Borg is an all-swallowing collective that cannot be resisted, a totalizing force.

Haraway‘s cyborg, on the other hand, is what might be termed a networked individual, illegitimate offspring of what Haraway calls the “informatics of domination,” but still subversive to the very forces that created her. S/he is an ironic hybrid of human and technology who breaks down binaries that otherwise seem naturalized and totalizing. The cyborg recognizes in technologies the possibility of “great human satisfaction, as well as a matrix of complex dominations. Cyborg imagery can suggest a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves.” (1991) The cyborg is complicit, a part of this digital world. But s/he is never entirely subject to its terms: s/he is not without agency.

The cMOOC as cyborg

So on the plane down to Theorizing the Web, as I finalized my slides, I decided that the first c in cMOOC stands for cyborg.

(I mean, I know it *actually* stands for connectivist. That’s as it should be. MOOCs were founded on the connectivist principles that knowledge is distributed and generative, and I think for MOOCs to actually capitalize in any sense on the affordances of digital technologies and not merely transfer traditional approaches to learning into the online space, those two concepts are important lodestars. And the original MOOC was built not only on George Siemens‘ and Stephen Downes‘ work developing connectivism but was actually a course ON connectivism and connected knowledge: the cMOOC model is connectivism incarnate.)

Because I’ve had the (sometimes admittedly discombobulating) pleasure of working with and in and around this grassroots model of MOOC for a few years now, I have a vantage point that many of MOOCs’ detractors don’t: I have lived experience of a model of MOOC that isn’t corporate, or colonial, or – most importantly – totalizing. And I think cMOOCs and other networked online learning opportunities and efforts that attempt to destabilize some of the institutional or corporate or globalizing tendencies that dominate much of the MOOC conversation (and many MOOCs themselves) may offer a cyborg approach to massive, open, online learning: it may offer a model of subversion.

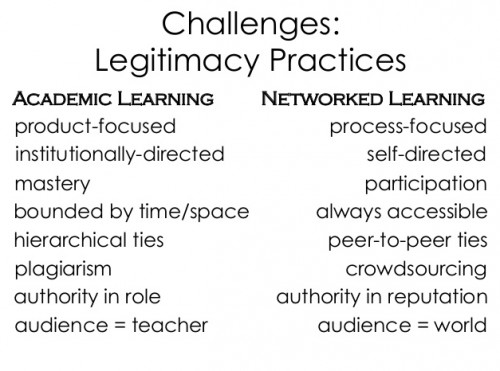

cMOOCs, even as cyborg, are neither a perfect model or a panacea for all the challenges higher education faces. But they emphasize participatory, networked, distributed approaches to learning that challenge and subvert many of our inherited cultural concepts of schooling. They encourage learners to generate knowledge, in addition to simply mastering it. They are a way to re-vision the conversation in terms that neither deny the possibilities of technology and networks nor give over entirely to the logics and informatics of domination.

They are MOOCs that undermine some of what MOOCs seems to be coming to mean, and in that, I think there is both power and potential.

***

current/ongoing/historical cMOOCs & their open/online/hybrid kin:

(including even a Coursera course that tries very hard to subvert its own conditions of production)

#etmooc (Educational Technologies MOOC – ongoing and amazing, just entering topic 4: check it & join in)

#moocmooc archives (two separate week-long MOOCs on MOOCs)

#ds106 (not a MOOC, but an ongoing, open, public course in digital storytelling via University of Mary Washington)

@dukesurprise (a for-credit Duke course with an open, public component)

#inq13 (a POOC or Participatory Open Online Course through CUNY on inequalities, with an East Harlem focus)

#edcmooc (a Coursera course in Elearning & Digital Cultures offered by University of Edinburgh that runs more like a cMOOC)

The MOOC Guide – Stephen Downes’ master resource of most cMOOC-ish offerings from the beginning

#change11 archive (the mother of all cMOOCs: 35 facilitators each took a week to explore change in higher ed)

There are lots more, I’m sure – happy to add if people want to send examples.