Next week is #dLRN15 at Stanford. Months of planning and debating and collaborating (and panicking!) all come together to launch an inaugural conference/conversation on Making Sense of Higher Education: Networks & Change.

It’s all Panic At The Disco around here these days, people.

***

There are some serious high hopes embedded and embodied in #dLRN15. Not just for a successful event – though a successful event is a joy forever, as the poets say. Or, erm, something like that. But success is a complex thing, and hopes go beyond the event.

#dLRN15 is grounded in the kind of quiet hopes most of us in higher ed these days don’t talk about all that much: the hopes that things can actually get better. The hopes that research can be conducted and communicated in such a way as to shape the direction of change. The hopes for a future for the spirit of public education, in a time when much in higher ed seems to have been unbundled or disrupted or had its goalposts moved.

Those kinds of hopes are waaaaay too big to lay on the shoulders of any single event or single collection of people…but still, we got hopes, and they underpin the conversations we’re hoping to start through this small, first-time conference next week. We have the privilege of bringing together powerful thinkers like Adeline Koh and Marcia Devlin and Mike Caulfield as keynotes, plus systems-level folks and established researchers and students and grad students and people from all sorts of status positions within higher ed, all thinking about the intersection of networked practices and learning with the institutional structures of higher ed.

However, there’s one strand of conversation, one hope, in the mix at #dLRN15 that I’m particularly attached to. It’s the Sociocultural Implications of Networks and Change in Higher Ed conference theme, and particularly the opening plenary panel of the conference, on Inequities & Networks: The Sociocultural Implications for Higher Ed. I’m chairing, and the ever-thoughtful George Station, Djenana Jalovcic, and Marcia Devlin have agreed to lead the conversation from the stage.

But we need you.

No plenary panel is an island…and while all of us contributing have our own deep ties to this topic, our role is only to start the conversation. Help us make it wider and take it further. Whether you’ll be there or not, your thoughts and input are welcome on the #dLRN15 hashtag or on our Slack channel, or here in the comments. Throw in.

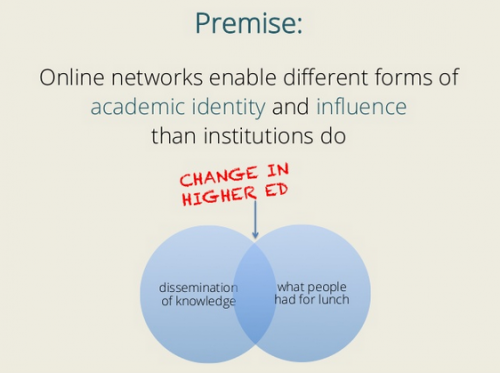

To me, this is the strand that gets at the heart of what education is for, and who it includes, and how, in a time of massive stress: is the digital helping widen participation and equality? Is it hindering?

If the answer to both is “yes,” WHAT NOW?

***

The aim of the panel is to explore how intersectional issues – race, gender, class, ability, even academic status – in higher education are amplified and complexified by digital technologies and networked participation. While digital higher education initiatives are often framed for the media in emancipatory terms, what effects does the changing landscape of higher education actually have on learners whose identities are marked by race/gender/class and other factors within their societies?

We’ll be sharing and unpacking some of the places we get stuck when we think about this in the context of our work as educators and researchers.

What effects do you see digital networks having on inequalities in higher ed? What sociocultural implications do networked practices hold for institutional practices? What are universities’ responsibilities to students who live and learn in hybrid online/offline contexts?

Please. Add your voices, so that this panel becomes more a node in a networked conversation than a one-off to itself. That in itself would pretty much make #dLRN15 a success, in my mind. :)