One morning, all my friends woke up as experts.

Or rather, thanks to years of what academia had mostly framed as the gauche and wasteful habit of talking excessively to people who lived inside our computers and iPads, many of us whose social and work lives had merged somewhere in the ether of that Third Place/Space woke up with workshops to give, because…academic service. When what was gauche and time-wasting yesterday is The New Black today, it’s handy to have a vanguard of self-taught experts to teach everybody else how to play along.

But what are all these workshops doing, in the context of the academy? Mark Carrigan posed the question of social media as fashion or fad on Twitter this morning. I retweeted his post. We ended up in a conversation that eventually included another three or four colleagues, from a few different countries. THIS is how social media actually works for me, when it works.

These excerpts carry the gist of the conversation better than I can encapsulate. They also raise questions that I think all of us passing as social media gurus – however unwillingly – in the academy need to grapple with, and soon.

- Are the workshops helping…or just making people feel pressured to Do Another Thing in a profession currently swamped by exhortations to do, show, and justify?

- Does the pressure over-emphasize the actual power of social media and encourage people to dig in against it as some kind of new regime, without necessarily having the experiential knowledge to judge whether it could have any value for them?

- How do we understand and frame the benefits of digital and networked scholarship? (In my research, participants pointed to a gap between the “it increases your citations!” stick used to exhort academics to use social media for scholarship, and the actual carrots of connection and being able to contribute to the conversation in one’s field.)

- How SHOULD we count digital and networked scholarship within the academy? Should we count it at all?

FWIW, I think we should, but I’m very wary of how. And so I wonder what happens the morning after we all wake up as experts, so to speak.

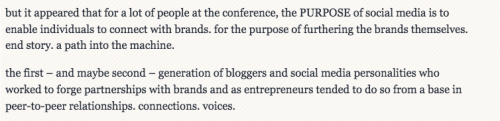

I feel like I’ve been here before. Yesterday afternoon, somebody tweeted an old post I wrote four years ago, back when I’d had a personal blog for years and was trying to understand the shift I was seeing in the economy of social media, from relational to market.

It was the words “a path into the machine” that gave me a sense of deja vu.

Because one morning back in about 2008 all my friends woke up as social media gurus. We’d been hobbyists and bloggers and it was kind of wonderful but faintly embarrassing to talk about in polite company and then BOOM people started appearing on Good Morning America and it gentrified and stratified fast.

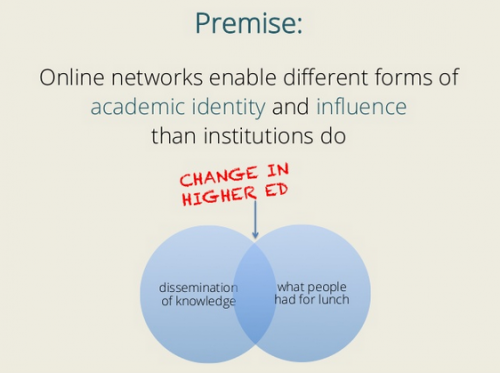

Switch out “brands” for “institutions” up in the pull quote above and we are living a parallel moment in academia, just a few years late. And the the many-to-many communications that the networks were based on risk, once again, being instrumentalized into something broadcast-based and metrics-driven that misses the whole point.

There has been plenty of excellent – and necessary – advocacy for the inclusion of digital, public engagement in academic hiring and tenure and promotions and our general sense of what counts as scholarship.

But the practices that get encapsulated as digital scholarship or networked participatory scholarship straddle two worlds, and two separate logics. One is the prestige economy of academia and its hierarchy and publishing oligopoly and all the things that count as scholarship. The other is social media, which has its own prestige economy.

So if those of us giving workshops to the academy about social media don’t make it really clear that it’s more than metrics – and don’t give people the experiential opportunity to taste what a personal/professional learning network (PLN) feels like and can offer – we have only ourselves to blame when the academy eventually tries to subsume social media into its OWN prestige economy.

The morning is now, kids. It’s been now for a little while but it won’t be forever. Seize the day.

How do YOU think we can best engage scholars and institutions in networked scholarship without selling the farm?