I read another article yesterday on The Death of Twitter: they’re multiplying, these narratives, just like the fruit flies in my kitchen.

Like fruit flies, these lamentations for Twitter do not spontaneously generate, but are born from a process of decay: they are the visible signs of something left neglected, something rotting quietly out of sight.

Since I’m currently in the extended throes of researching Twitter for my dissertation, I read these articles like I used to read Cosmo back when I was twenty: half-anxious that Enlightenment will be contained in the next paragraph, half-anxious it won’t. When I was twenty, I had Cosmo to make me feel miserable about the gap between what I valued and what I saw reflected and valued by the world. These days, I have The End of Big Twitter.

I wonder about what it means to research something changing so quickly, so drastically. Will my dissertation end up being about the Twitter that was, rather than whatever it is in the process of becoming? Can a person become an historian by accident?

Is this all there is to say, anymore?

Because once there was more, at least for me. Way back in the arcane days of 2006 and 2007, I went to live among another culture – participatory culture, in its heyday – and felt at home for the first time. A particular confluence of privilege and obscurity and the need to speak things I had no place to speak aloud contributed…and the experience was mostly good. Not always ideal, by any means, but networks and Twitter in particular opened for me whole worlds of conversations and ties that I would never – flat-out – otherwise have had access to. And those conversations and ties have shaped my identity, my work, and my trajectory in life dramatically over the last eight years. Yet I sense the conditions that made all that possible shifting, slipping away.

I do not know what comes next, at this strange intersection. This post is My Own Private Fruitfly: its lifespan short and humid. It may be dead or obsolete in fifty days. But it is what I see, here and now, on the heels of a sweltering and disturbing August.

***

“The Death of Twitter” is Not About Twitter

I’m no great fan of their recent platform changes and even less of the likelihood that they’re about to make what I see in my feed far more algorithmically-determined, a la Facebook. But I don’t think a new platform will arise to save what’s getting lost and lamented about Twitter. The issue all the articles point to is about Twitter As We Knew It (TM) as a representation of an era, a kind of practice. At the core, it is about the ebbing away of networked communications and participatory culture – or at least, first-generation participatory culture as I knew it, as Jenkins is perhaps best-known for describing it.

It is also about the concurrent rise of what I *hope* is peak Attention Economy.

(Of course, the founding premise of the Attention Economy is there’s no such thing as too much Attention Economy, so yeh, I’m probably wrong on the peak front .)

Consolidation of the Status Quo

Some of this is overt hostile takeover – a trifecta of monetization and algorithmic thinking and status quo interests like big brands and big institutions and big privilege pecking away at participatory practices since at least 2008.

…Oh, you formed a little unicorn world where you can communicate at scale outside the broadcast media model? Let us sponsor that for you, sisters and brothers. Let us draw you from your domains of your own to mass platforms where networking will, for awhile, come fully into flower while all the while Venture Capital logics tweak and incentivize and boil you slowly in the bosom of your networked connections until you wake up and realize that the way you talk to half the people you talk to doesn’t encourage talking so much as broadcasting anymore. Yeh. Oh hey, *that* went well.

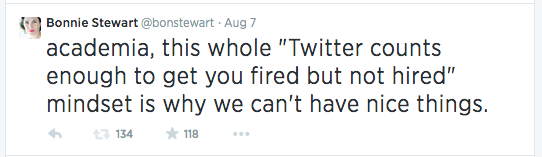

And in academia, with Twitter finally on the radar of major institutions, and universities issuing social media policies and playing damage control over faculty tweets with the Salaita firing and even more recent, deeply disturbing rumours of institutional interventions in employee’s lives, this takeover threatens to choke a messy but powerful set of scholarly practices and approaches it never really got around to understanding. The threat of being summarily acted upon by the academy as a consequence of tweets – always present, frankly, particularly for untenured and more vulnerable members of the academic community – now hangs visibly over all heads…even while the medium is still scorned as scholarship by many.

You’re Doing It Wrong

But there’s more. The sense of participatory collective – always fraught – has waned as more and more subcultures are crammed and collapsed into a common, traceable, searchable medium. We hang over each other’s heads, more and more heavily, self-appointed swords of Damocles waiting with baited breath to strike. Participation is built on a set of practices that network consumption AND production of media together…so that audiences and producers shift roles and come to share contexts, to an extent. Sure, the whole thing can be gamed by the public and participatory sharing of sensationalism and scandal and sympathy and all the other things that drive eyeballs.

But where there are shared contexts, the big nodes and the smaller nodes are – ideally – still people to each other, with longterm, sustained exposure and impressions formed. In this sense, drawing on Walter Ong’s work on the distinctions between oral and literate cultures, Liliana Bounegru has claimed that Twitter is a hybrid: orality is performative and participatory and often repetitive, premised on memory and agonistic struggle and the acceptance of many things happening at once, which sounds like Twitter As We Knew It (TM), while textuality enables subjective and objective stances, transcending of time and space, and collaborative, archivable, analytical knowledge, among other things.

Thomas Pettitt even calls the era of pre-digital print literacy “The Gutenberg Parenthesis;” an anomaly of history that will be superceded by secondary orality via digital media.

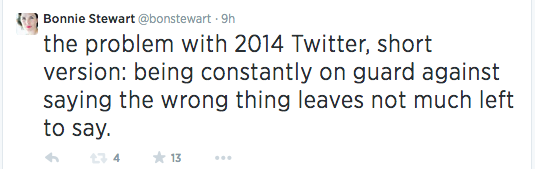

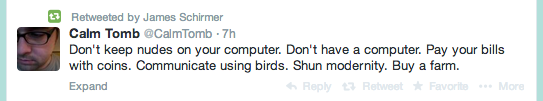

Um…we may want to rethink signing up for that rodeo. Because lately secondary orality via digital media seems like a pretty nasty, reactive state of being, a collective hiss of “you’re doing it wrong.” Tweets are taken up as magnum opi to be leapt upon and eviscerated, not only by ideological opponents or threatened employers but by in-network peers…because the Attention Economy rewards those behaviours. Oh hai, print literacies and related vested interests back in ascendency, creating a competitive, zero-sum arena for interaction. Such fun!

Which is not to say there’s no place for “you’re doing it wrong.” Twitter, dead or no, is still a powerful and as yet unsurpassed platform for raising issues and calling out uncomfortable truths, as shown in its amplification of the #Ferguson protests to media visibility (in a way Facebook absolutely failed to do thanks to the aforementioned algorithmic filters). Twitter is, as my research continues to show, a path to voice. At the same time, Twitter is also a free soapbox for all kinds of shitty and hateful statements that minimize or reinforce marginalization, as any woman or person of colour who’s dared to speak openly about the raw deal of power relations in society will likely attest. And calls for civility will do nothing except reinforce a respectability politics of victim-blaming within networks. This intractable contradiction is where we are, as a global neoliberal society: Twitter just makes it particularly painfully visible, at times.

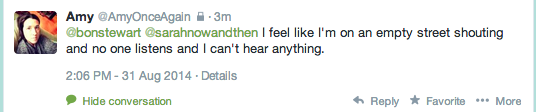

Impossible Identities

Because there is no way to win. The rot we’re seeing in Twitter is the rot of participatory media devolved into competitive spheres where the collective “we” treats conversational contributions as fixed print-like identity claims. As Emily Gordon notes, musing about contemporary Twitter as a misery vaccuum, the platform brings into collision people who would probably never otherwise end up in the same public space. Ever. And that can be amazing, when there are processes by which people are scaffolded into shared contexts. Or just absolutely exhausting. We don’t know how to deal with collapsed publics, full stop. We don’t know how to talk across our differences. So participatory media becomes a cacophonic sermon of shame and judgement and calling each other out, to the point where no identity is pure enough to escape the smug and pointless carnage of petty collective reproach.

Somewhere, Donna Haraway and her partial, ironic, hybrid cyborg weep, I think.

This doesn’t mean I’m leaving Twitter. I’m not leaving Twitter. If this post is a fruit fly signalling rot, it is likewise the testament of a life dependent on the decaying platform for its sustenance. The fruit is still sweet, around the rotten bits. And there is no other fruit in the basket that will do so well.

***

Perhaps it is not rot. Some would call it inevitable, part of the cycle of change and enclosure that seems to mark the emergence of all new forms of working and thinking together. I’m not so sure: that still smells to me like high modernity. Either way, I will miss Twitter As We Knew It (TM)…but I wonder: what am I not seeing yet? What paths of subversion, connection, hybridity are still open?

I’m over by the fruit bowl, listening.