It’s a brand new year, people. Four days in, and my brain is still rife with metaphors of new-fallen snow and fresh starts and resolute setting of goals.

But for all the rhetorical power of these conceptual flights of potentiality, I am stuck with the distinct feeling that the old year bloody well followed me home and sits lolling about on my desk, laughing at my attempts to clean slate and begin anew.

“Wherever you go, there you are,” an old friend used to say.

Where I am is still last year’s business. In fact, if 2012 really *was* the Year of the MOOC, I’ll be cozied up with last year for the next three months straight.

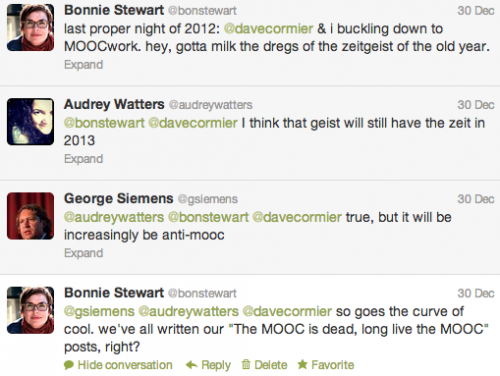

The night before New Year’s Eve, I joked on Twitter about Dave & I buckling down to work on the MOOCbook before the zeitgeist of the old year passed.

This morning I opened up my poor neglected blog and discovered the draft of this post, begun in July and last touched in late October, titled, in fact, “the MOOC is dead, long live the MOOC.” Apparently the joke is on me.

That’s the thing about MOOCs. They’re so everywhere that I can’t even keep track of what *I’ve* thought about them in the past couple of months, let alone the other copious buckets of ink spilled on the topic.

The whole damn thing has gotten so vast. And I feel as though it’s anathema to the current professional climate to ever admit one is overwhelmed, especially early in the new year, when one is supposed to be washed clean of all that baggage.

But there it is. Wherever you go, there you are.

***

Looking around at the broad higher ed/edtech scene, I suspect talking about MOOCs in productive ways is getting harder for everyone.

When there’s a clamour of voices, identifying the places and positions people are speaking from, let alone what’s left to be said, can be an assault from all directions. Trying to research MOOCs and write speculatively about what they may imply for higher ed is a lot like working in the midst of a big ol’ maelstrom. Mostly composed of verbiage.

Traditional models don’t suffice. Good research tends to try to be clear about which shoulders of giants it stands upon, and which gap in knowledge it aims to address. MOOCs are still such a moving target that the gaps in knowledge and direction aren’t really yet clear. And news reporting thrives on a heady mix of sensationalism and actual change, both of which are beginning to wear thin.

Because the biggest obstacle to effective conversation about MOOCs is that none of us IN the conversation – even the biggest names – appear to be clear yet on what MOOCs are or can be, or on where they begin and end.

As Dave put it in his inaugural appearance in ye olde fancy Wall Street Journal, “Nobody has any idea how it’s going to work.”

I’d go a step further, beyond the business model aspect of the conversation. I think the challenge with MOOCs, at this juncture, is that nobody has any idea what they are. This makes talking about what they *can be,* let alone their effects on what *is* in contemporary higher ed, rather a challenge.

Roger Whitson nailed it back in August after the first #MOOCMOOC experiment, with his Derridean claim of “il n’y a pas de hors-MOOC” or There is no-outside MOOC; there is nothing outside the MOOC.

We *know* what we mean when we talk about higher education, or at least, we believe we do. We have a broadly agreed-upon societal understanding of where the perimeters of that conversation lie. In fact, the perimeters of that conversation have traditionally lain more or less where MOOCs begin.

But where do MOOCs end? If we are talking about experimentation with learning online, on any kind of mass scale, are we then talking about MOOCs? How do we distinguish one possibility from another?

A year ago, MOOCs themselves were a rather small experimental niche; a loose but vibrant network of learning focused around principles of connectivism and openness and distributed, generative knowledge. Then Sebastian Thrun opened up the AI course at Stanford: to those for whom MOOCs were familiar, the term fit.

George Siemens called the AI course a MOOC back in August, 2011. The media gradually caught up, because there was no other equivalent term. When Thrun founded Udacity and the hype began to build, the word “MOOC” followed. And the rest, as they say, is history. Rather accidental history.

One of the most fascinating things about the proliferation of MOOC buzz is the way in which it’s made visible the networks by which media and higher ed make knowledge today.

But here we are, wherever we go. MOOCs mean video lectures. Or they mean distributed, aggregated means of making new knowledge. Or they mean democratization, or disruption, or whatever other Christ-on-the-cross people want to hang their futures on.

So how do we talk about the Internet happening to education without getting hopelessly mired in Wittgensteinian language-games? How do we begin to sort out and advocate for what we want MOOCs to be, when conversations about them tend to immediately point out that participants are speaking from entirely different reference points and hopes and belief systems?

I wish I knew. That’d be a heady way to start the new year. Instead, all I know is too much is being conflated under this bubble, as if everybody just woke up and noticed the internet might actually be relevant to higher ed. In that sense, I almost hope the 2012 narrative around MOOCs *is* good and dead, much as I doubt the calendar shift simply erased it.

But I also know that this messy, paralytic conversation remains one of the liveliest things I’ve ever participated in professionally, in almost twenty years in the field of education. The idealist in me says that if we don’t know where MOOCs end, then maybe their possibilities are still grandly open.

For me personally, the value of MOOCs has been primarily in belonging: in finding ways to connect and learn and share within otherwise too-broad networks. In that spirit, then, I’ve signed up for two new (connectivist-style) MOOCs this month – #etmooc and the second #MOOCMOOC – in the midst of the book-writing and thesis-researching on the subject. I’m hoping the more active engagement will help rejuvenate my own sense of the meta-conversation, and where to speak from.