So, the Typhoid Mary of education disruption, Sebastian Thrun, has admitted that venture capital interests are not well-suited to the complex structural realities of public education, and moved on to professional and corporate training.

Ding dong, the MOOC hype is dead.

(Yes, Audrey Watters and Mike Caulfield are both quite right: this doesn’t mean venture capital is moving out of education’s purview, nor can educators just “shrug off lousy educational practices because they occur outside the walls of formal education.” Agreed. But the professional training end of education has always been a business: it’s never had the same public and societal responsibilities, nor scope of systemic challenges.)

Yes, we need to talk about venture capital’s incursion into education, even at the corporate training level. And we also need to talk about what it means to pitch the promise of education as social mobility in a society where the promise of jobs is actually pretty scant. We need to talk about academic labour in higher ed’s increasingly adjunctified system. We need to talk about the ways in which institutional higher ed both supports and penalizes students, by nature of its systemic structure. We need to talk about pedagogies for utilizing the internet to teach cheaply and widely. We need to talk about the fact that Udacity was allowed to conduct its Silicon Valley-style “fail fast” experiment on public (and largely minority) students at San Jose State. All of these are connected conversations, broadly.

But if the “solution” of venture capital MOOCs is off the table, maybe we can stop getting mired in the plate of shiny red herring it pretends to offer to all these real issues, and actually work on them. Maybe across some of the fault lines the hype has created.

To me, Thrun’s change of course changes the whole discussion, because it forces the flaming hype of MOOCs as replacements for systemic education to separate into the multiple conversations that have been conflated under that rhetoric for more than a year. Udacity’s about-face may not prove the VC model for education won’t work, but it sure lays out the fundamental disconnects between shareholder accountability and messy public education real nice.

Let’s talk about that.

Yesterday’s news might even mean we stop talking about MOOCs at all, since Thrun’s putting distance between his new initiatives and the word (Rolin Moe looks at this and the whole Udacity announcement in far more complexity here). Makes sense. By definition, corporate training is structured to be neither massive – even in possibility, as it’s bounded by the corporation’s limits of who belongs and who qualifies – nor open.

Then, those of us interested in what massive and open can mean, learning-wise, can go back to whatever we decide to call networked open online learning, aka the MOOCs outside the venture capital model. As George Siemens said this morning, “Make no mistake – this is a failure of Udacity and Sebastian Thrun. This is not a failure of open education, learning at scale, online learning, or MOOCs.” Or, in Martin Weller’s words: “Does this mean MOOCs are dead? Not really. It just means they aren’t the massive world revolution none of us thought they were anyway.”

I come to bury hype, not to praise it.

***

…And in terms of what I think MOOCs are, here’s a taste of a small, semi-open one I’ve really enjoyed being a part of this past week.

I’m one of the facilitators and participants in the #wweopen13 MOOC on Online Instruction for Open Educators. I’m teaching a short conceptual-ish introduction to the idea of networked identities, for people interested in teaching online.

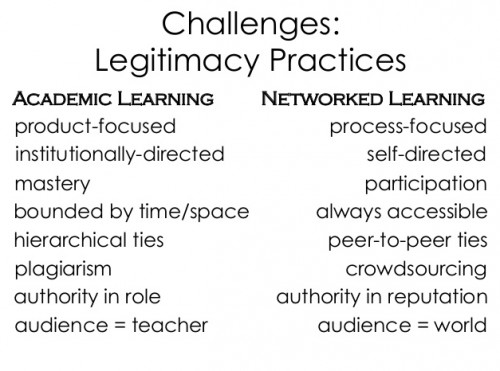

Yet the institutional structures and norms that dominate our society and particularly our education system do not foster networked identities. In the midst of all the pressure for educators to somehow prepare students for this mythical “21st century” we seem to be both living in yet still casting as the eternal and exotic future, the whole fact that schooling practices are broadly structured to create herd identities of compliance and uniform mastery rather than networked identities of differentiation is…well…not surprising. But definitely a disconnect.

Here’s the slideshow from my live sessions this week, exploring my ever-expanding “key selves” of digital identities as well as some of the benefits and challenges of identity work as a connected educator, and a cameo from Freire.