I want to talk about open. And academia.

And the outmoded gatekeeping process of the dissertation, world’s most glorified and inflated five-paragraph essay.

***

Last week was Open Access week, and just before I got on a plane for Australia, Dave & I coordinated a series of Lightning Talks at UPEI about a bunch of different facets of open, and cool things people are doing on campus. There was a GONG. It was fun. I talked about doing my dissertation research in the open…and managed to limit myself to talking for *only* five minutes. There were bets.

Then I went to Australia and talked for waaaay more than five minutes. One talk was specifically on academic Twitter but the other was more me trying to frame out the whole open scholarship thing for folks new to digital pedagogy. I built out an ABC structure that I’m looking forward to digging into more deeply soon…and for the “blasphemy” piece I got to talk Donna Haraway so I was happy.

THE ABCs OF OPEN SCHOLARSHIP:

Then I flew homewards and I was unhappy for approximately 32 hours. I swear the whole “let’s do Sunday twice over with zero connectivity and connections timed so you never seem to go to sleep” gig was harrowing. My mental health and I had to just grimly dog-paddle our way through screaming newborns and back spasms and tiny tiny seats, trying to hang together and forebear. We made it, ragged and ghastly, just in time for Hallowe’en!

Which is my segue into dissertating, because hey…there are parallels.

***

OPENING THE DISSERTATION

I am not getting on any more planes this week, though a part of me wishes I were. #OpenEd16 at VCU in Virginia starts today. A Very Large Proportion of my personal/professional “everybody” is there, and while Dave and I had hoped to be too, in the flesh, we are not. Life.

But we are part of a couple of panel conversations about open, including one tomorrow that launches the followup from last year’s #dLRN15 – go check out #SoNAR, the Society for Open Narrative Research.

But this narrative is about the OTHER panel.

Opening The Dissertation: Exploring the Public Thesis Spectrum is Friday afternoon, a hands-on session with Laura Gogia and Jon Becker. I proposed the panel back before I, erm, realized I totally couldn’t go. It was supposed to be us and my committee member Alec Couros and Sava Saheli Singh and Katia Hildebrandt…but. Life. Sigh. Yay Laura and Jon for picking up the slack!

I proposed the panel because for all I shared much of the process of my dissertation research here on the blog, there was a great deal that remained an unspoken long strange trip that no trip back from Australia can hold a candle to.

I want to open up the dissertation to the light of day.

To some extent, this conversation is about open dissertations and open defences. Laura and I both opened up our defences in various ways, with the support of our supervisors and committees, so that our broader networks – who, in both cases, were the subject/s of our research – had a window into the event itself. Mine was livestreamed, right up to the end of public questions. Laura’s was livetweeted by invited guests, right through the committee questions.

Laura, being a visualization wizard, has created a chart around the different decision points involved in opening up dissertation and defence processes to public audiences, and I’m looking forward to participating in the exploration of these – and the possibilities and risks involved – via Google Docs, on Friday. If you’re at #OpenEd16 and you’re in any way part of anyone’s dissertation process, come and join this conversation and help us gather ideas and possibilities!

But. I didn’t actually propose the panel *just* so we could all have a clearer and more granular picture of where we can potentially open up dissertations and defences.

I wanted to open up the question of what – and who – the dissertation is FOR.

OPENING THE CONVERSATION

Laura’s most excellent flowchart captures many of the decision points in the dissertation process where openness is concerned, but it misses what I think of as perhaps the core one – audience.

Not in the specific sense of the audience who sit in the room or even in front of a screen to witness a colleague outline the work they’ve brought to fruition – but in the sense of the eyes and ears and understandings and policies that thesis work eventually touches and shapes.

The capacity to choose real-life audiences – and to be supported in preparing to *address* real-life audiences – matters. In my day job, I work in adult ed. Done well, adult ed and professional learning are all about meaningful choices and application and authentic audiences for student work.

But when it comes to preparing scholars for the so-called pinnacle of higher education, the doctoral degree, the emphasis FAR too often is on having Ph.D students spend years of their lives preparing a very long, highly-format-focused piece of writing primarily for the audience of their defence committee – THREE TO FIVE PEOPLE, usually – and whoever wants to check the damn tome out of the library in ensuing decades.

Yes, scholars often adapt their dissertations for academic books or papers, but these separate publications usually involve another few YEARS of rewrites and edits from Reviewer #2 before they ever see the light of day.

We need to talk about this, academia.

Here’s my opening salvo for Friday’s presentation in Richmond (complete with sticky note diagrams, sailing metaphors, and upside-down boats):

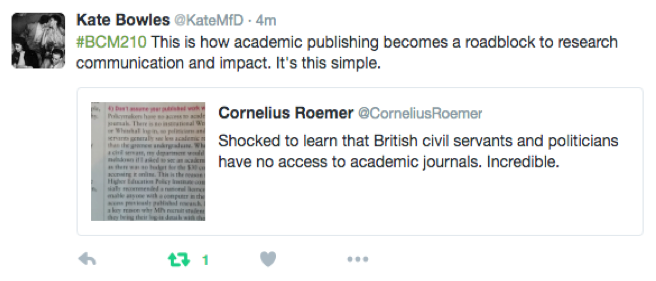

Long story short, the status quo does not help us make a case for the value of higher ed and expert knowledge. Already we lock away too much of our research in expensive, inaccessible, and increasingly unnecessary journals because we’re attached to our own prestige economies. We miss the opportunity to get that research – knowledge that takes years and, often, public funds to develop – TO THE PUBLIC via policy and media and open channels.

But with the dissertation situation, there’s something particularly ugly about our continuing attachment to familiar forms.

Outside continental Europe, most senior scholars’ concept of the dissertation defence or viva is a tradition of intimate questioning behind closed doors, a rite of initiation, almost.

But…initiation into what?

We are no longer training for the professoriate. Any pretense that that is what the Ph.D dissertation and defence processes are for in their entirety should be met with a Come-to-Jesus about both casualization AND contemporary scholarly practices. We lived in a credential-inflated world, and there are few long-term stable jobs left in higher ed for those who complete even its highest degrees. Even when their tuition and cheap grad student/post-doc labour keeps the system afloat. Full stop.

In my own dissertation work on open and networked scholarship, I found one of the biggest benefits *repeatedly* cited by participants was that cultivating open, public audiences for their work and ideas allowed them to “contribute to the conversation” in their field and in higher ed generally, EVEN WHEN THEY DID NOT HAVE STATUS POSITIONS IN THE ACADEMIC HIERARCHY.

This is where we get back to blasphemy. Haraway (1991) frames blasphemy as a form of faithfulness, an ironic and partial nod to profaned origins that nonetheless preserves the priority of those origins.

What are we being faithful to, when we engage in research, in Ph.D programs, in scholarship? A broken system, or the creation and circulation of knowledge?

How we do dissertations goes a long way to answering that question.

Graduate students embarking on a dissertation should be able to make informed, supported, meaningful choices about who the audience(s) for their dissertations should be.

One of the prime responsibilities of supervision should be helping students select, understand, and reach – to some scaffolded extent – those audiences.

And, OPEN SHOULD BE THE DEFAULT, RATHER THAN CLOSED. That doesn’t mean always, that doesn’t mean without supports. It does mean all of us IN the academy, no matter how precariously, need to learn to navigate various aspects of what it means to be part of the public conversation in our fields, so we can help students find meaningful ways to join in and contribute.

So, as I say in the video, let’s start this conversation. How do we open up the dissertation?