This Thursday – November 6th at 1:30pm – I’m a guest in George Veletsianos’ #scholar14 open course, talking about networks as places of care and vulnerability. It’s a Google hangout, so the talk will be an informal back and forth, open (I hope?) to multiple voices if folks want to join in.

It may even be a little bit fraught, as George may have had a different concept of vulnerability in mind when he first suggested the topic. He frames vulnerability in terms of sharing struggles, which I’ll definitely talk about on Thursday; my online origins lie deep in the heart of that territory. But, the juxtaposition of care and vulnerability, as a topic, was rich enough it that it helped me grapple with some of the complexities I was trying to frame from my research study, and I took up vulnerability more through a lens of risks and costs. As I am wont to do, I ran with that lens, and ended up not only with the presentation below (liveslides from Alec Couros and Katia Hildebrandt’s EC&I831 class last month) but with half a research paper under that working title for my ongoing dissertation project. So. Yay for networks.

Join us Thursday for the fisticuffs over sharing v. risk. Or something like that. ;)

More seriously, I may have ended up in a somewhat different place than George envisioned, but it’s a place I think needs to be visited and explored.

The Risks and Costs of Networked Participation

I just spent a week almost entirely offline, for the first time in…oh…about a decade. Not an intended internet sabbatical, but a side effect of extended theme park adventuring with small children and a phone that turns into a brick when I cross the US border. Y’all were spared an excess of gratuitous commentary on the great American simulacra that is Disney, basically. You’re welcome.

Being disconnected from my network was kind of refreshing. No work, no ambient curation, no framing and self-presentation for a medium with infinite, searchable memory.

It didn’t mean I was magically present the whole time with my darling offspring: I remain a distractible human who sometimes needs to retreat to her own thoughts, online or off. Nor did it mean I missed out entirely on the surge of painful yet necessary public discussion of sexual violence, consent, and cultures of abuse and silence that bloomed in the wake of Canada’s Craziest News Week EVER. Still. Sometimes a dead phone is a handy way to cope with the overload and overwhelm of networked life, especially for those who both consume and contribute to the swirl of media in which we swim.

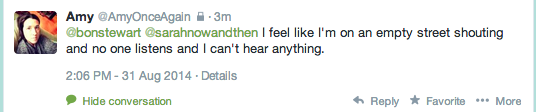

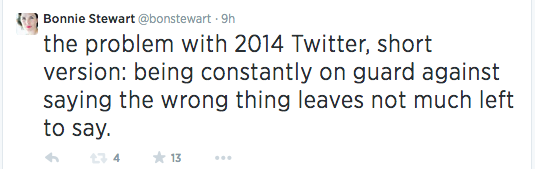

Because contributing and participating, out in the open – having opinions and ideas in public – has costs.

***

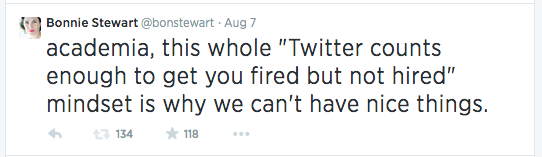

Participation makes us visible to others who may not know us, and makes our opinions and perspectives visible to those who may know *us,* but have never had to grapple with taking our opinions or positions seriously (oh hai, FB feeds and comments sections hijacked by various versions of #notallmen, #notallwhitewomen, and #notalltenuredscholars).

Participation enrols us in a media machine that is always and already out of our control; an attention economy that increasingly takes complex identities and reduces them to sound bites and black & white alignments.

The costs are cumulative. And they need to be talked about, by those of us who talk about networks in education and in scholarship and in research. Because in open networks, a networked identity is the price of admission. The costs are what one pays to play. But they are paid at the identity level, and they are not evenly distributed by race, gender, class, orientation, or any other identity marker. And so with participation comes differential risks. This matters.

Bud Hunt pointed out in a (paywalled but worthwhile) Educating Modern Learners article this morning that October was Connected Educators Month…and also Gamergate. Two sides of the participatory coin. Audrey Watters doubled down on that disconnect this afternoon in Hybrid Pedagogy, riffing on Dylan’s Maggie’s Farm and asking edtech to take a good, hard look at what we ask of students when we ask them to work online:

“And I think you need to think about your own work. Where you work. For whom.

And then you must consider where you demand your students work. For whom they work. Who profits. Where that content, where that data, where those dimes flow.”

– Audrey Watters, 2014

So. This post comes, like Bud and Audrey’s pieces, from a growing dismay and uneasiness with what’s happening at the intersection of technologies and capital and education; a growing belief that the risks and costs of networked identity are an ethical issue educators and researchers need to own and explore. It comes from looking through my research data for what Audrey calls “old hierachies hard-coded onto new ones.”

***

Attending to Each Other in the Attention Economy

But it also comes from the sense that there is more; that the ties created even in the most abject, hierarchical, surveilled online spaces tend, like good cyborg entities, to exceed their origins.

It comes not just from the formal research data collected over months of ethnographic observation and conversation, but also from some deep and powerful conversations that the research process created.

I didn’t know Kate Bowles especially well when I put out the call for participants in my dissertation project a year ago today. She didn’t know she had breast cancer when she agreed to participate. Somewhere along the road of the past year, our discussions of identity and networks and academia and self and life sometimes got beautifully tangled, as ideas actually do, freed from eureka-moment idealizations of authorship. And somewhere in the middle of one of those tangles, she reminded me that my sometimes grim vision of the attention economy is not the only way to conceive of attention at all; that its origins come from stretching towards and caring for each other.

“the attention economy…isn’t just about clicks and eyeballs, but also about the ways in which we selectively tend towards each other, and tend each other’s thoughts–it’s an economy of care, not just a map to markets.”

– Kate Bowles, 2014

I don’t know what to make of all that…but there’s hope in it that I’m not willing to abandon just yet. When I think about networked scholarship right now, it’s in terms of these contradictions of care and vulnerability, all writ large in the attention economies of our worst and better angels.

Maybe on Thursday, in the #scholar14 hangout, we’ll figure it out together and I’ll know how my paper should end. ;)