This week, Mia Zamora and I are kicking off #digciz 2017 with a conversation about digital citizenship, and what it means in a world wherein “the digital” is increasingly a delivery system for surveillance and spectacle and amplified uncertainty.

(Or maybe that’s just my take. Maybe it’s different in your world. Maybe you see it differently? I would pay big cash money to see it differently so I am open to being invited over. Please note I actually have no big cash money.)

In any case, the month of June will be a #digciz-fest of epic proportions *if* y’all come out and play, and Mia and I have the privilege of leading us all out of the gate with a few provocations and a #4wordstory conversation about what good citizenship means in participatory spaces.

Here’s my opening salvo. :) (I’m a bit of a shit about the word “citizenship”…)

Grumpy Cat, ultimate Digital Citizen, makes the perfect Rorschach Test for your own interpretations of digital citizenship! Is he saying:

a) Even online, we are all people. Kumbay-effing-yah.

b) Digital citizenship sucks because people. People suck.

c) It is irritating to even have this conversation. Stop being a digital dualist.

d) All of the above?

***

I myself am still not entirely sure. A little over a month ago, I wrote up a talk on citizenship and identity that I didn’t manage to explain very articulately…and got comments like it was 2008 up in here.

Note to self: PUBLISH HALF-BAKED LIGHTBULB MOMENTS MORE OFTEN.

Or rather: publish half-baked lightbulb moments more often, *if* you like the hit of attention/engagement/validation that comments apparently still provide, even years after blogs were supposed to be dead.

(Disclosure: I am actually that person who likes the hit of attention/engagement/validation that comments apparently still provide, just if there were any questions. But we do not acknowledge that publicly, do we? Because decorum. Or the games we play around palatable identities in an attention economy.)

Only my discomfort with totally half-baked posts – or the rarity of lightbulb moments in my life – will save y’all from wanton comment-chasing, folks.

Which brings me back to the actual lightbulb moment that I’d had in the middle of that talk I tried to write up.

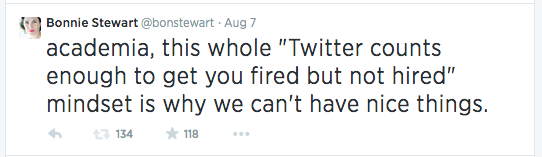

Digital platforms and digital affordances – underpinned by the capitalist enclosure of participatory digital spaces over the last decade or so, with its surveillance and metrics and constant advertising of reductive versions of our identity back to us – do NOT lend themselves to good digital citizenship, in the sense that they do not foster a space I would actually want to be a citizen of, to whatever (limited) extent the citizenship model holds when conceptualized in the border-free digital realm.

They do not lend themselves to good digital citizenship because they shape and direct human behaviour in ways that privilege capital and circulation and extremes, rather than, say, collaboration or empathy. Or even just being alone with one’s thoughts.

They increasingly shape the logic of our learning spaces to Silicon Valley’s concept of what that should be. Spoiler: that tends to be “individualism, neoliberalism, libertarianism, imperialism, the exclusion of people of color and white women.”

They foster spectacle and scale and virality and dogpiles and dragging and while there are moments of justice and glory in it all, at its logical endpoint it’s a Hunger Games.

(Wait. Mixed my dystopias.)

Of course, if you’re reading this, chances are good you don’t live in that web, that digital space. Humans have agency. Technologies or platforms are not determinist. I read my comments section. Got it.

Most of the people who’ll ever click on this post will come to it through the variety of still-quite-participatory communities that form my network, and our collective constellation of “digital” remains very much not-entirely-subsumed by capitalism and spectacle. We resist. We share. We care.

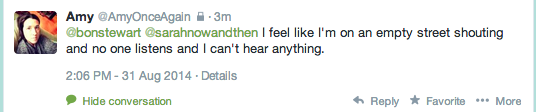

My research was really clear about the caring, the ways in which we make ourselves vulnerable to each other, even in the strange collapsed contexts of academic Twitter.

I’d venture that in most digital spaces that build any sense of ongoing community over time, people do the same. That‘s why I’m a bit of a shit about citizenship.

***

The web, and the capacity of strangers to receive my words – all of them, even the ugly ones or the half-baked ones or the things I couldn’t say out loud – once gave me back some sense of myself as being able to contribute to a world I wanted to live in.

It gave me a sense of being a citizen – in the rights and responsibilities sense, in the belonging sense – of something I was invested in more than I’ve ever, frankly, been invested in the concept of Canada as a nation-state (no matter how much Trump has done recently to make me appreciate that particular concept and its vulnerability, AHEM).

But the operations of scale and visibility and capital – especially capital – mean that our platforms keep creeping up on us, shifting, creating all kinds of insidious ways to monetize our caring and our sharing and in doing so, shape how we relate to each other…and in the long run, who we get to be in relation to these digital spaces.

And nope, #NotAllPerformativity is negative and #NotAllSoCalledSlacktivism is empty, but platform-based and -driven behaviours that shape our sense of personal identity should be things we’re watching WAAAAY more closely than we seem to know how. Not just because we may be frogs boiling slowly towards whatever Mark Zuckerberg’s end game of world domination may be…but because polarization seems to be eating us alive, as a broader society, online and off.

The fracturing of social bonds and security is not digital. The inequality and uncertainty at the root of it is not digital.

But it all leaves us…confronted. Constantly confronted.

And the digital amplifies our confrontedness.

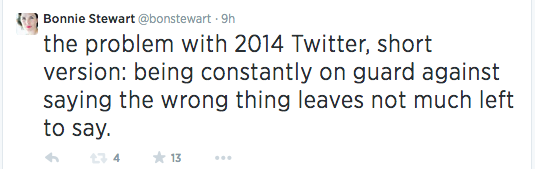

The digital demands constant signalling. Other people’s signalling confronts us. We create spaces to bond over that confrontedness. Performative wokeness devolves into factionalism. White supremacy festers its way into the open.

This seems to be the yearbook quote of humanity confronted by virtue signalling:

And then, as a FB friend quipped in the thread under my earlier identity/citizenship post…we get caught “in the crosshairs of the split hairs.” THAT.

I think THAT should be 2017’s yearbook quote.

And because we are human, we don’t even always completely notice the way our identities are being shaped by our social environments and what they naturalize…THEY JUST BECOME OUR REALITY.

***

So…what can we do? How can we envision and work toward something better? What kinds of civic and social spaces do we want, online?

Tell us your #4wordstories of what YOU want, using the hashtag #digciz.

The conversation will unfold for 48 hours or so, through June 1st. Or whenever we’re done. Our goal is to get a sense of what people think digital citizenship can be, but also to hash out some of the constraints and realities that shape what it is, for most of us. And what works. What we could be aiming for, as a model of human engagement.

Just a little model for human engagement. You know. Shoot the moon. ;)

In exchange for keeping Slovak workers out the war effort, they agreed to deport their Jewish population, whose roots in Slovakia went back 500 years. In the deal, the “

In exchange for keeping Slovak workers out the war effort, they agreed to deport their Jewish population, whose roots in Slovakia went back 500 years. In the deal, the “