(This one’s long. Sorry.)

Ronald Wright’s A Short History of Progress (2004), quotes John Steinbeck as saying:

“socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but temporarily embarrassed millionaires” (p. 124).

This expression has stuck with me for nearly a decade.

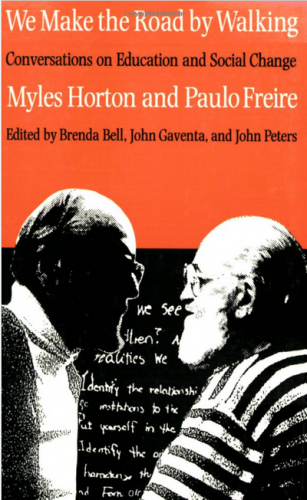

When I first read it, it sent me back another decade or so to a small book I read when I first went back to school after teaching in the Arctic.

A little red book, but not THAT little red book. Still, a book that brought ideas of communal action and adult education home to me, in a very literal way.

Myles Horton and Paulo Freire‘s We Make the Road by Walking is one of those dialogic educators’/theorists’ conversations captured as texts that education faculties were very fond of teaching from in the late 90s. It was my intro to adult education as a field and an ethos, and in a sense, a reintroduction to my own Maritime history and sense of place.

It was my introduction to the idea that education need not be a lofty enterprise separate from the lived experience of being somewhere, and from somewhere.

With the death of Fidel Castro last weekend – and even my own FB feed making evident the vast difference in the narratives Canadians and Americans have been sold about Cuba over the past nearly sixty years – it feels maybe *too soon* to be talking about socialism and public education and communal action.

But with the election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency this month – to which my FB feed had a more coherent response of pretty broadly-distributed OH SHIT – and his appointment of the Amway-adjacent & public-school-attacking Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education, it feels maybe too late NOT to be talking about public education and communal action, at least. (I can take or leave the socialism, depending on the interpretation. It’s the totalitarianism and cults of personality I’m wary of.)

And here we circle back to the temporarily embarrassed millionaires.

(Bear with me. I swear all these synaptic connections cross.)

***

One of the interesting parts about coming of age as an adolescent and (semi)conscious citizen of smalltown PEI, Canada, in the 80s was that – in spite of lacking both social media and cable TV – I inhabited two equally-confusing places simultaneously: my own latter-day Avonlea, with its dour social mores passed on relatively unchanged since their airing in Anne of Green Gables, and Reagan’s America.

I lived in both.

I was a kid of the 99 Luftballons era. I listened to the words…and I wrote poems about nuclear disarmament to the United States President. I did not write to my local mayor, or to Trudeau Senior.

As the twelfth-grader is to the ninth-grader in the classic high school pecking order, so the US is to Canada on the world stage of power and Mother Do You Think They’ll Drop the Bomb? I learned to understand that whatever risks nuclear weapons posed to my possible survival in that brief window of the reheated Cold War, when I was twelve, it wasn’t a matter of President Reagan *wanting* to blow me up in any personal rendition of The Day After.

(I realize now he’d likely have been hard-pressed to find PEI on a map.)

But in a place tacked onto the edge of the continent and economically downtrodden for the better part of a century or more, you gradually figure out that you’re not at the centre of anyone’s calculations about the world.

***

What this has to do with Horton & Freire is all about education, to me.

(NOT education as a simple, linear path to success and prosperity for the marginalized…or those who think they are. That’s a complex mythology that tends to serve up false expectations and disappointment, at best, across cultural, racial, geographic, and economic marginalization. Not that there are necessarily better answers, only that the playing field Simply. Does. Not. Level. On those fronts, read Sara Goldrick-Rab on the costs that education exacts from those least prepared to pay, and Tressie McMillan-Cottom on the link between for-profit schools and increasing inequality.)

I’m thinking more in the vein of adult education.

In We Make the Road by Walking, one of the threads of conversation between Horton and Freire – the one that stands out most in my memory – is this question of whether systematized education can be transformational for marginalized people(s), or whether it replicates all the inequalities baked into society’s/societies’ existing systems.

Horton and Freire, lions of educational practice and leadership in their own Appalachian and Latin American contexts, have differing perspectives on this, with Horton asserting that change within a system gets co-opted by the system itself, while Freire suggests a “one foot *in* and one foot outside” approach to systematized learning.

My own career has been more in the vein of Freire. I work for an institution, however precariously.

But in the context of these strange days of Trump’s pre-presidency, I find myself drawn to concepts that go beyond the boundaries of institutions as ways of trying to rethink education and communal action and where we all go from here.

Concepts and initiatives like #4YOS – four years of individually-pledged, distributed service as means of fighting hate in local, concrete ways. Efforts to make communities stronger, more inclusive places.

For myself, I’m particularly interested in how we fight the strange cocktail of victimization and entitlement that hate leeches onto and deploys in its service. I’m interested in how media and social media are part of the problem, and what we do about it.

I’m also interested in the not-solely-American concept of the temporarily embarrassed millionaire. The person – whatever their economic circumstances – clinging to idealized privilege in the rearview mirror with their cold dead hands. Sure that Trump’s gonna make them a contender again.

I went looking for historical models for what to do about this mess, systemically. And Horton was the first person I thought of, because the temporarily embarrassed millionaires have always – somehow – made me think of Horton.

Horton and Lilian Wyckoff Johnson, a teacher and professor, established the legendary (and interracial) Highlander Folk School in the mountains of Tennessee during the Great Depression. It was both an educational and political space, for organizing and training labour unionists while conserving and enriching the local cultural values of that specific geographic place. Highlander later served as a site for Civil Rights and social justice organizing, and ultimately had its charter revoked under accusations of communism. It re-incorporated as the Highlander Research and Education Center, and continues to do work in local leadership training, environmentalism, and economic justice.

Highlander operated outside systematized, institutional, formal education.

Part of me thinks whatever we’re going to do now, we don’t have time to wait for systematized, institutional, formal education to address the blossoming of outright bigotry that Trump’s election seems to have released on both sides of the border (I mean the US and Canada, for those of you used to the word “border” meaning Mexico). The system can catch up later if it wants.

But Highlander had a Canadian equivalent that fewer people outside my neck of the woods know about.

It was called The Antigonish Movement, a Maritime adult education, cooperative, and microfinance movement of the 1920s and ’30s that led to the development of local credit unions that still dot the landscape around Maritime Canada. Its vision was as education-focused as it was economic: it was a vision of human emancipation. And for all it was a relatively radical movement for its time, it had its roots in two stalwart institutions of Maritime Canada: the Roman Catholic Church and the extension department of St. Francis Xavier University, located in a tiny little rural industrial town called Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

The Antigonish Movement centered around the endemic poverty and marginalization people in these small rural towns experienced.

Geographic marginality is often a marginality of benign neglect rather than overt oppression, at least where the ongoing benefit of systemic white supremacy operates. But – and particularly in the economic context of the 1920s and ’30s, before Canada had any form of social safety net – benign neglect can nonetheless result in grinding, structural, seemingly inescapable poverty. And this experience – among others – can produce temporarily embarrassed millionaires, who feel victimized by their lack of what they perceive as their rightful status, but are disinclined to examine why.

The Antigonish Movement was about examining why. It was formed to fight the “weird pessimism” of constant outmigration from the Maritime provinces and its attendant social attrition and decay among those who remained. It was about working collectively to change that.

It was about the idea that the “local economy could be revitalized if the right type of learning was cultivated in ordinary people: especially critical thinking, scientific methods of planning and production, and co-operative entrepreneurship.”

The Antigonish Movement had three key structural components: mass meetings, which Extension Department members organized with community members from villages and towns around the entire region, study clubs, wherein community members gathered together in local homes to study materials available on economics, cooperative principles, and business organization, and the School for Leaders, wherein members of the study clubs could attend six-week programs at the university in Antigonish, to prepare people for action and minimize business failures.

In the late 1930s, at the peak of the Antigonish cooperative influence, there were 1100 study clubs around the Maritimes, with 10,000 participants. Wikipedia says, “by 1938 these study clubs had formed 142 credit unions, 39 co-operative stores, 17 co-operative lobster factories, 11 co-operative fish plants, and 11 other co-ops.” In provinces as small as these, it is impossible to over-estimate the human effect of this level of industry and change.

***

They used technology as part of this educational change process.

I remember learning about Antigonish back at the time I first read We Make the Road By Walking, and a prof told us stories of Father Moses Coady, one of the great lights and voices of the Antigonish Movement, using radio to broadcast to communities and villages throughout the Maritimes.

I thought about that as this post germinated the other day and I began to wonder what a modern-day Antigonish Movement would look like, could do.

The original was about collaboration and cooperation to address poverty and people’s lack of understanding and agency regarding their own circumstances. To me, at this current moment, it is our societal lack of understanding and agency regarding media literacies and digital literacies – and thus the stories we tell ourselves about truth, decency, and each other – that is the poverty I know how to address. To ask “why” about.

Media literacies as an educator has been what I *do* for the better part of twenty years. I have a Ph.D in Twitter and social media, more or less. And yet the contemporary media landscape and the fake news and the climate change news and the mainstream media’s failure to consistently label white nationalism by its name all have me overwhelmed.

If I am going to learn and teach against this tide I won’t be able to do it alone.

Could we? Together? In a systemic, local-global organized fashion? Is there value in an Antigonish 2.0?

The mass meetings would be easy, I think. We would need each other for study groups. We could break out the best of what we all bring to digital and media literacies and dig in hard until we figure we can see behind the curtain for a moment. We could then start our own local study groups/digital literacies initiatives in our own contexts. I personally happen to coordinate a Maritime university adult ed program – not *quite* an extension department, but hey – that I’d love to use in a School for Leaders capacity, if that part is still relevant.

I believe that education is a process of offering people tools – conceptual as well as technical – to understand their identities and possibilities and those of others within a structural framework that points to various paths of possible agency.

The temporarily-embarrassed millionaires won’t all be interested, nope. But is there something here, in examining the why and how of contemporary #digitalliteracies in ways that help people understand the systems shaping all our lives, that could make a difference?

I’m curious. I’m listening. I invite your ideas and feedback.