(this post is crossposted from #Antigonish2.com)

***

November. Rolling on an Amtrak train across North Carolina, on my way to Triangle SCI. Our team – one of six chosen for the Institute, woot! – will spend four days in Chapel Hill working on scholarly storytelling and digital storytelling. I’m here because of #Antigonish2 and its emphasis on participatory engagement models…I’m excited to see where the conversation leads.

But the journey is a story already, really.

This is the first Amtrak train I’ve ever been on. I heard Tom T Hall songs on a jukebox in Charlotte last night that I hadn’t heard in years. This is a part of the world I only know from books and songs. Just being here feels like some kind of peak Americana.

We just whistled past a little brick house by the side of the tracks with a big hand-painted sign in front of it that reads “THANK YOU JESUS.”

It leaves me wondering about the versions of North Carolina I am prepped to recognize and absorb, and all I’m missing. Whose stories I’m missing because they were not the stories I grew up on as my own/not my own, north of the border but somehow part of a shared dominant cultural narrative. I think about Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie’s “The Danger of a Single Story.”

I joke on FB that I flew from Charlottetown to Charlotte – both named after the same 18th century British Consort – and the airport promised me Billy Graham but I ended up with Burt Reynolds & I’d call it a win. All true. Still odd to visually revisit the white patriarchs of my 70s-80s childhood.

Anyway, I am here. Trying to tell it is never the same as the experience.

I am thinking about about storytelling as experience.

Academic and scholarly forms of storytelling – or knowledge dissemination, if you prefer the formal term – don’t tend to privilege the experiential. They tend to be abstracted, content-focused. Yet I keep seeing a FB link about how we can’t change people’s minds just with facts and content…I can’t find this FB link thanks to spotty train wifi, of course, and maybe it’s fake news (edit: it’s here, thanks Bob Gray!)….but with a grain of salt or two, I think we might want to begin to consider – from the big picture of academe – what we lose when we tell our stories the way we do. For the often-intentionally limited audiences we frame ’em for.

On the plane yesterday I read a blog post by Keith Hamon in which he explores the #MeToo hashtag as hyper-object and experiential…that there is no unity or single artifact to emerge from the hashtag, but rather the noise is the point. I also read an article in which major alt-right Twitter personas were just outed as Russian trolls. So much of what has shaped public narrative in the last 16-18 mos is still something we don’t fully have literacies to process, because tactical uses of Twitter make possible the unleashing of any narrative into an experiential environment that can convert biases and prejudices and positionality into perceived reality, into things people can’t unsee or unknow.

The combination of the two pieces got me thinking that being literate in a hashtag world involves recognizing that media are now experiential, full stop.

We are part of the circulation of this entity we cannot grasp as a whole. We need a new focus on literacies to make sense of it all…that was always the point of #Antigonish2…but the idea that they may be experiential literacies is one I’ve been bumbling towards. I hope to dig into more deeply this week.

And I want to find ways to put those diggings out there, where others can join.

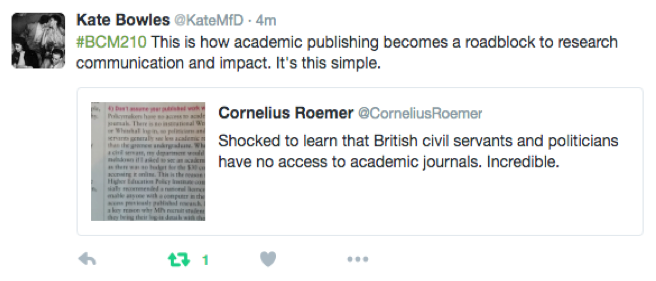

When academic stories – academic knowledge – are mostly tied down in restricted and expensive journals and specialist language and reliant on journalists and audiences busy with nuclear threats and Nazis in the streets and catastrophic natural disasters and shootings, what gets lost?

This is what I’m thinking about, rolling across North Carolina with Amtrak spotty wifi.