This week I got to descend upon Ohio – and OSU’s annual Innovate conference – to give a keynote about networks and higher education.

Here are the slides I used to try to tell the story I was trying to tell:

Funny story about that story.

Innovate’s theme for this year was “excellence,” with a focus on, as their site put it, “sharing innovations that let educators re-imagine their instruction without sacrificing pedagogical quality and rigor.”

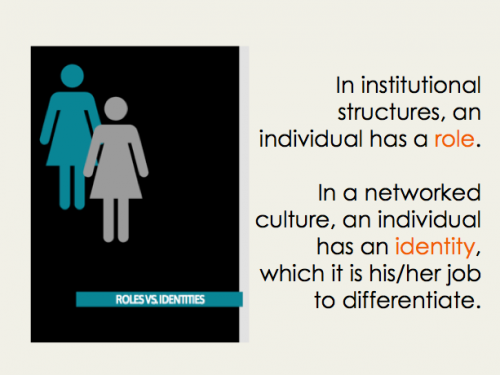

Now, I’m not in the habit of making claims about excellence. Or innovation, or even rigor, unless I’m in the throes of a formal academic paper in which case I can dig into ontologies and epistemologies and validity structures and make a case OSU’s own Patti Lather would be proud of. A language of excellence and innovation and rigor tends to emphasize performance rather than learning, and while that’s important for funders and decision-makers it doesn’t necessarily map tidily against ideas of connection and vulnerability. My work is still deeply steeped in the logics of the social web, if aware of that perspective’s limitations…and the forces that aim to eclipse it.

But they clearly knew all that. The ad for the talk read:

I laughed out loud when I read that first sentence. And I decided to approach “excellence” with some of the same wry touch they’d brought to the keynote blurb.

I enrolled my kids’ copy of Where the Wild Things Are to help illustrate the story. I talked about networked practice and its implications for higher ed as The Wild Rumpus.

Where the Wild Things Are won Maurice Sendak the 1964 Caldecott Medal for Most Distinguished Picture Book. *That,* quite frankly, is about as safe a marker of excellence as you’re gonna find in the fraught world of higher ed these days, and not just because it’s a kids’ book: rather, that’s how the prestige economy of recognizable, institutionalized legitimacy works.

People have heard of the book, and the Caldecott medal, so the recognizability of the title and the award would serve as proxies for quality, I figured. If you’re going to introduce all kinds of new practices to a group of academics, best to start from a safe place. A signal that resonates. Kinda like when someone says, “I went to Princeton” or “I published in Nature.” Those titles are signals. I have (shhh…don’t tell) never read Nature and I’ve never been to New Jersey, but I have been acculturated enough to academia that I understand that both the journal and the college signal a level of widely-recognized prestige that I’m supposed to be impressed by.

Because that’s how prestige operates: that “supposed to” interpellates people and recruits them based on aspirational identity…the desire to be the sort of person who *gets* that kind of thing. So in academia, outside of our own very specific disciplines, we trade entirely on these broad, external signals. That’s how academia manages to function as a broad in-group in spite of the fact that most of our knowledge bases are so extraordinarily specialized there’s no way for a chemist to actually tell if a sociologist does good work or not, or vice versa. The signals are stand-ins for the actual knowledge we possess.

Entertainingly though, in the process of establishing broadly understood signals – where people went to school, who they’ve studied with, where they sit in the academic hiring hierarchy, where they’ve published, who’s funded them – those signals themselves get reified and the prestige accorded them comes to seem entirely natural.

Yes, Nature has the highest impact factor of all journals…but how many academics can actually explain impact factor, pressed to the point? Princeton is Ivy League, which means something even to us heathens up in Canada, who totally fail to recognize many of the prestige signals of US academia.

(Imagine the dismay and betrayal I felt when, after half a lifetime of hearing the words “Ivy League” bandied about as Americanized synonyms for “Oxford” and “Cambridge,” I discovered the Ivy League IS AN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE. Huh????

I digress.)

Long story short, I figured Where the Wild Things worked as a proxy for excellence in the tiny context of my talk because while both the title and the medal are recognizable, nobody’s gunning for either. Neither the book nor the wild rumpus – even as metaphor – has been declared the next Great Tsunami or Disruption, so nobody’s career or reputation ride on making sure that everybody is clear how mightily it sucks. Plus the book is sweet and nostalgic and most people don’t really remember what it’s about, they just remember how it makes them feel. Which is also how signals operate.

And *that* is how I tripped my own self up on and almost had to ditch the whole thing half-baked in the middle of the journey to making a case for the networked Rumpus as its own form of excellence.

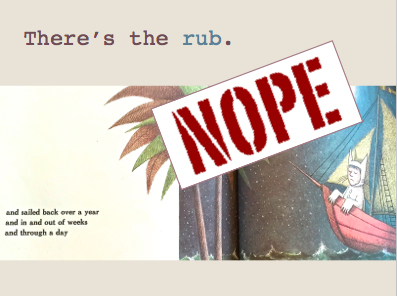

Because I was thinking of The Wild Rumpus as a metaphor for some of the spaces outside the boundaries of conventional prestige signals, just a fun way of talking about an alternative prestige economy, when I realized I should probably re-read the damn book. RESEARCH.

I’d forgotten, of course. Max – the little blighter at the centre of the story who runs away to the fantasy world of the wild things in his fantasies – ends up wanting to go back where people love him best of all and his food is still hot. The rumpus is joy and freedom and the wild things bow down to his taming, but in the end he sails home to his bedroom, back to normal, back to the glorious comfort of the known.

The Wild Rumpus is just a distraction, for Max. Whoopsie.

But in the middle of knowledge abundance and precarity and disinvestment in public education, a world where over 70% of North American higher education instructional staff were reported to be contingent even back in 2007, I think it’s safe to say that most of us won’t be sailing home to our solid tenured realities when we’re done with the fun of our contemporary Rumpus.

So I made this slide, and turned the story sideways…a bedtime story to wake up conference attendees first thing in the morning. Not a happy ending, but the unpacking of the Rumpus outlines ways to navigate the seas of abundance and change, at least.

***

Post-script: I wish I could say my ideas will change the direction of the ship and bring us home to where supper is still hot.

I tell myself it is wiser to grow up and learn to forage with Wild Things.

I don’t know. The Rumpus has treated me extraordinarily well, but contingency is a flawed and exhausting place to live. The potential networked practice brings to higher ed – the particular versions of excellence it makes possible, the ones outlined in the slides above – are still by far best enacted by faculty and staff with the security to take risks, and iterate. But that’s often not how it works out. Higher ed is an increasingly stratified professional environment, and networked practice may increasingly be seen as a signal of LACK of prestige, as power circles coalesce around the privilege they conflate as excellence.

Maybe THEY are the Wild Things and we can tame them with Max’s magic trick of staring into their eyes and telling them, “Be Still!”

No? Dammit. Now I will not sleep tonight.