This is the first post in a series outlining my ethnographic study of identity positions in online scholarly networked publics.

It is a way of beginning to write out my research in a context with fewer formal constraints than publishable academic writing will demand. It is also a way of communicating with participants and with my own networks about how I’m beginning to make sense of the work I’m doing. It’s a space wherein people can comment/add/speak back to the ideas I’m exploring, before I trap them in the amber of print format.

Lastly, it’s a trail of breadcrumbs: I’d like to be able to look back from wherever this research eventually leads me and trace some of the process of getting there. It’s here for the nibbling:no guarantees about where it will lead, but anyone else thinking about ethnography in the open is free and welcome to make use of it too.

***

Step One: Find Volunteers

In November of 2013, I put out a call for research participants via my blog and Twitter. Scholars, I said, are you on Twitter? Can I come live like a fly on the wall of your networked publics for awhile and look at how influence, credibility, and identity positions work in your online worlds?

They said yes. Bless them, they said yes.

I’d wanted twelve participants, maximum – ethnography is about depth, not about quantity – but I was floored by the volume and generosity of responses I got. Nearly thirty volunteers responded to the open call, and I tapped a few more by following up on previous expressions of interest in the project.

Step Two: Select Participants

Then, the great cull. Of all the things I’ve done with this project in the last three months, this was by far the most challenging. It wasn’t technically hard – I had a pretty tight set of requirements that I’d laid out in advance and made public in the call – but the act of choosing and owning my choices involved internalizing methodology and enacting its particular rigour upon myself.

The long, circuitous research and writing phases of my thesis proposal, intense and personal though they’d been, had involved some separation of self from work. The intensely reflexive process of challenging, adapting, and coming to own the analytic framework I’d developed in the proposal dissolved that comfortable distance. The process of selecting participants from a rich pool of volunteers – many of whom I knew, respected, and wanted very much to build or maintain positive network ties with – was the point at which I came face to face with the power and risk inherent in the identity position of “researcher.” It is one thing to understand that research “worlds” particular constructions of human value and knowledge into being, and another to actively prepare to stand openly and nakedly alongside those constructions and the selection process they represent, ever in conversation with their premises and conclusions.

My methodological approach is rooted in Patti Lather’s (1986) critical ethnography work on reconceptualizing validity and Donna Haraway’s (1988) assertion that all knowledges are situated in a view from somewhere. My goal was to try to explore as broad a range of somewheres as I could, within the limits of my own monolingualism and the norms of small sample size within ethnography. My project aimed for geographic and ethnic diversity, for range among volunteers’ institutional roles and network scales, and for representation from a variety of sociocultural identity positions. My research call read:

The research will be conducted in English and will focus on identity and reputation-production within the English-speaking global academic sphere. Participants from a range of geographic locations, academic career stages, and disciplines are preferred, with mixed gender representation. The ways in which cultural identity markers and marginalities affect reputation and networked practices will constitute a part of the study: representation is sought from outside culturally-dominant groups in terms of ethnicity, sexual orientation, class origins, and other markers.

I made an Excel spreadsheet and lined my volunteers up within it. I followed each volunteer on Twitter, and checked out any blog links they sent, all the while hoping for some kind of magical Exacto knife that would enable me to select from the bounty of offers without, y’know, damaging relationships or the potential for relationships. I looked through each person’s profile carefully…with the exception of one lovely and non-recriminatory soul I met a month later who responded to my “You should have been in my research!” exclamation with a slightly confused, “Um…I volunteered. You never wrote me back.” Whoopsie. Two white female Ph.D students from Texas wrote me within hours of each other. I totally conflated the two in my head. My error, and my loss.

I eliminated people I would have loved to work with, because they did not have blogs, or current institutional affiliations within academia.

I eliminated people I was shocked to find myself crossing out, only because I had so many others who lived where they lived or who shared similar identity categories.

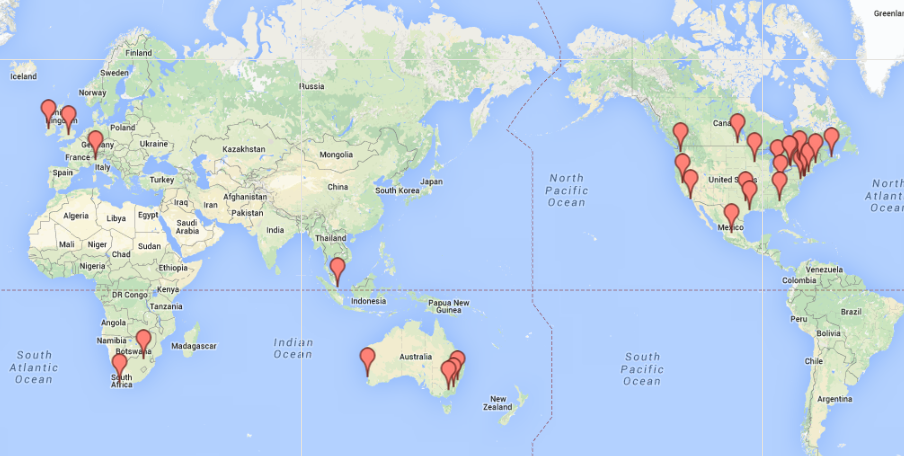

I made a map, so I could see the patterns and gaps left on a globe. I make no claims to speak for any parts of the world in this research, even the part I inhabit: at the same time, I think this visual of the locales of actual volunteers makes the situatedness of this project and whatever knowledges emerge from it very vivid. Note the huge swaths of human society from which I heard not a peep.

Within the areas I did hear from, homophily was an issue: nearly half of the volunteers turned out to be white Ph.D students, as I am. A third were also concentrated in eastern North America, where I reside. Only seven of the thirty were male. None self-identified outside traditional cisgender categories. Seeing all this laid out onscreen reinforced for me the importance of trying to design for diversity of voices: even though my call for participants was shared at least 150 times (as visible from within my Twitter account alone) and circulated far beyond the borders of my known networks, the majority of those who stepped forward bore some categorical commonality with my own identities. This reality made me ruefully aware of the ways in which my research will, like all research, reflect my own situated knowledge(s) as well as those of participants, whatever the efforts I make towards multiplicity.

Step Three: Who’s on Board?

In the end, I could not pare down to twelve participants. I chose fourteen, intending to interview at least eight…and assuming a couple might not necessarily complete the reflective tasks requested.

(I also chose another eight who agreed to act as exemplar identities for the others to reflect on: these folks were not formally participants but allowed me to explore with participants the ways in which they perceive and read the identity and reputation signals others share online. I am deeply grateful to the exemplars, as I am to every one who stepped forward to offer their names, their interest, their support, and their amplification of the call for participants.)

So. I’ve had the privilege, these past three months, of engaging in Twitter-based participant observation with these twenty-two people. Of the fourteen active participants, a couple have lived their networked lives doubly-situated: in Mexico and Vancouver; in one case, in Singapore and Western Australia, in another. Seven more are based across North America, one is in Ireland, one in South Africa, two in Australia, one in Italy. Ten are female; four male. Nine self-identified in the initial expression of interest either as “white” or effectively unmarked (ie. no disclosure of racial or ethnic heritage); the others identified respectively as black and US Southern, Malay, Latino, half-Indian, and Jewish. Four identified as gay or queer. One identified as autistic. One disclosed HIV-positive status during the course of the research. Another found out she had breast cancer the same week we began the research process. These various identifications formed some of the texture of our communications, to varying degrees: the intersection of embodied identities and identity positions with what networked publics enable and constrain was a part of what the research project was intended to dig into.

Three participants were entirely unknown to me before they expressed interest in the research, four were loose ties whose names I knew without much awareness of their work, four were moderately well-known to me, and three were individuals with whom I’d had fairly extensive networked interaction over the previous couple of years. (I’d met two of the three close ties in person, in academic conference settings). Seven are Ph.D students or candidates at various stages of completion, two of whom also hold longstanding secure administrative or teaching positions within their institution. Three are early career scholars, one on tenure-track. Three are senior professors or researchers within their institutions – one has recently transitioned from a longstanding educational consultancy role within an institution to a research professor appointment there – and one is a director on a five-year alt/ac contract with a research institution. The majority are in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. In terms of scale of networks, their Twitter accounts range from a few hundred followers to thirteen thousand followers. Among the exemplars, there is even greater range in scale. Academic disciplines represented by the twenty-two participants and exemplars include but are not limited to Communications and Culture, Educational Psychology, History, Chemistry, Rhetoric and Writing, Online Learning and Educational Technologies, Public Administration and Political Science, Literature, Social Work, Information Technology, Anthropology and Sociology, and Education.

It’s been an extraordinary couple of months. Participants’ generosity in terms of time, intimacy, and tolerance for my almost-constant presence has been remarkable, as has their ongoing contribution to my research not *just* as participants but as resources and curators of a pretty steady stream of meta-information related to my study. The real challenge of networked research, I suspect, is information abundance – at the end of three months’ intensive observation, I not only have thousands of favourited tweets and dozens of blog posts to wade through as data, but literally hundreds of journal and news articles shared by participants that *may* reflect on the research questions of identity and scholarship, and may shape the course of my own meaning-making. If I can manage to read them without drowning.

So that’s where my research began, and with whom. Next time, I’ll take up the how of doing ethnography via Twitter, and how I grappled with the identity challenges of looking at…identities. :)