I’ve been thinking a lot about institutions lately. In trying to trace a narrative line through the sturm und drang around MOOCs and all that they make visible, I’ve been digging into institutional histories, trying to understand what the hell happened in the last thirty years. Who switched the terms of the game of higher education?

I’m looking at you, market forces.

For those of us raised in the world that Stanford researchers in the 70s called ‘the New Institutionalism’ – a world where education’s entire organizational structure was understood to place it firmly “beyond the grip of market forces” (Meyer & Rowan, 2006, p. 3) – it’s all gotten rather bewildering. Many managed not to notice the stealth incursion of for-profit institutions and Pearson into the world of academia (related: the student populations these corporate entities have served, via ESL textbook empires and “the MBA you can probably get into” ads, have not been the white middle-class that still codes “default university student” in North America. Ahem. Just sayin’.). But MOOCs, with their posh ties to Harvard and Stanford and their grandiose claims of revolution, sorta blew that stealth game out of the water.

MOOCs as Enclosure

This past week alone, Coursera moved into professional development for teachers and announced a partnership with Chegg, an online textbook-rental company, to connect MOOC learners with select, limited-time access to texts from large publishers. As Audrey Watters notes, these shifts are beginning to look like the enclosure of education against the very openness that MOOCs began from: “What was a promise for free-range, connected, open-ended learning online, MOOCs are becoming something else altogether. Locked-down. DRM’d. Publisher and profit friendly. Offered via a closed portal, not via the open Web.”

This enclosure is about profit models, not learning. And it profits few, in the end, because – as I got het up about in Inside Higher Ed last week – the societal mythology of education as value really only functions if institutionalized credentials in some way tie to social mobility and lucrative work.

That’s not the game we’re in, anymore.

But here’s the thing: MOOCs are a symptom of change in higher ed, not the source of it. We need to find ways of talking about this enclosure of openness by profit models, without conflating these forces with online ed in general or even entirely with MOOCs.

Because we will not resist the corporatization of education by standing solely for conventional institutionalized models. That horse has left the barn. But in online practices there may still be ways to protect and preserve some of the broad societal concept of the “we” that institutions were intended to enshrine.

MOOCs as Symptom: Networks + Neoliberalism

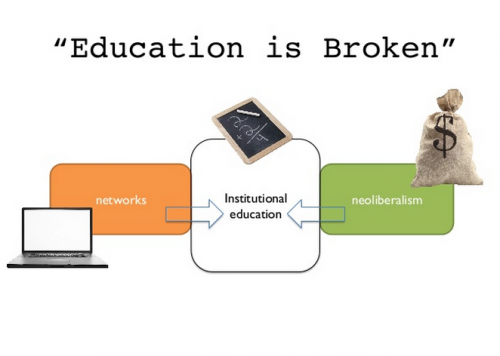

Basically, this is where we are: traditional institutional education is being encroached upon from all sides. And the big MOOCs conflate the two primary forces for change: networks and neoliberalism.

This is an ugly slide – I kinda like to call the clip art “retro” – but it’s the best illustration I have at the current moment for what I see actually happening to higher ed as we’ve known it. From one side, what George Siemens terms “the Internet happening to education,” or the networked opening of what was conventionally the closed domain of knowledge. From the other, the market incursion into the sphere of education, with its attendant ideological leanings towards the measurable and the profitable.

Last week, Dave & I went to two conferences together. We do the majority of our conference travel independently, so even getting to be at the same events was kind of exotic for us: being invited together was a treat. But blending our two separate strains of thought into a single keynote for the second conference was something we haven’t done in a couple of years, since all the MOOC stuff blew up.

We bickered about process: that’s par for the course, for us. We’ve worked together as long as we’ve known each other, and while our ideas and even perspectives tend to complement the other’s, our ways of getting there are pretty much opposite. (Sidenote: our writing on the MOOCbook has been pretty much two solitudes, enabling us to continue our lawyer-free relationship.)

But in the process of pulling together, between the two of us, three hour-long presentations to be delivered over the course of three days, on separate but intertwined topics, something converged and snapped into focus.

I’ve been looking at networks from an identities perspective for a few years now, trying to understand who we are when we’re online and what it is about this whole experience that actually matters, from an education perspective. Dave’s been wending his way through an exploration of rhizomatic learning as a way of navigating uncertainty within an era of knowledge abundance. Both of us have been thinking a lot about MOOCs and what they mean for change within higher ed. Hell, most of our household income comes from academic institutions, so the current budget crunch hits home.

But it became clear this week that our work needs to be about finding ways to use networks to push back against the neoliberal vision of the future of education. About making clear that the two do not share the same set of interests.

The conflation of the two is everywhere. Salon has an interview with Jaron Lanier today that makes the case that the Internet killed the middle class. Lanier’s arguments conflate networks with neoliberalism, making the latter invisible as a force unto itself. Sure, there are places where networked practices rely on neoliberal approaches to the world, in the sense of Foucault’s “entrepreneur of the self.” And neoliberalism often co-opts networked practices and naturalizes the perception that the two are one and the same.

But I don’t think they are. At least…I don’t think they inherently are.

Whether they become so is up to us. Particularly those of us who share the values espoused by public education. We need to build our learning and teaching networks, share our ideas and our questions and our practices and what works and doesn’t, and refuse to be enclosed.

Institutional concepts of educational practices enclose easily: that is their nature. The transition from institutional models of the classroom to a massive for-profit textbook magnate’s version of the classroom isn’t really much of a transition, except in what gets lost in terms of public values.

Networks don’t actually enclose easily. Hence the idea of “participate or perish” that Dave & I came up with the night before our keynote at #WILU2013 in Fredericton: a new academic imperative for our times.

Don’t just publish, because the institutional models are encroached upon and becoming enclosed. Participate. Make things different. Don’t wait for it to be your “job:” that’s institutional thinking. Institutional jobs won’t be there if we let the profit models gut education entirely.

Here are our slides from WILU2013, which trace some of these ideas through our own research lenses.

And here are the slides from my Spotlight Speaker session at CONNECT2013, where I focused in more detail on the participation and networking side of things: on how to go beyond institutional identities. Help yourself.

(Postscript: the “Education is Broken” Narrative as Sniff Test)

I want to return to this one in more depth…but a quick thought. The phrase “education is broken” gets thrown around a lot in the current educational climate. It is, in a sense, one of the key reasons neoliberalism and networks get conflated: it’s the area in which they agree.

But from one perspective, the idea that education is broken is a learning claim. From the other, it’s a credentialing and business model claim.

If you’re in the process of learning to tell the difference, don’t necessarily run from anything that claims education is broken. Rather, ask what aspect of ed it frames as broken. Is it the learning? You might be looking at a network. Is it the profit model and the structure and the means of offering credential? Probably neoliberalism and enclosure at work.

You’re welcome. ;)