I’ve been thinking a lot about institutions lately. In trying to trace a narrative line through the sturm und drang around MOOCs and all that they make visible, I’ve been digging into institutional histories, trying to understand what the hell happened in the last thirty years. Who switched the terms of the game of higher education?

I’m looking at you, market forces.

For those of us raised in the world that Stanford researchers in the 70s called ‘the New Institutionalism’ – a world where education’s entire organizational structure was understood to place it firmly “beyond the grip of market forces” (Meyer & Rowan, 2006, p. 3) – it’s all gotten rather bewildering. Many managed not to notice the stealth incursion of for-profit institutions and Pearson into the world of academia (related: the student populations these corporate entities have served, via ESL textbook empires and “the MBA you can probably get into” ads, have not been the white middle-class that still codes “default university student” in North America. Ahem. Just sayin’.). But MOOCs, with their posh ties to Harvard and Stanford and their grandiose claims of revolution, sorta blew that stealth game out of the water.

MOOCs as Enclosure

This past week alone, Coursera moved into professional development for teachers and announced a partnership with Chegg, an online textbook-rental company, to connect MOOC learners with select, limited-time access to texts from large publishers. As Audrey Watters notes, these shifts are beginning to look like the enclosure of education against the very openness that MOOCs began from: “What was a promise for free-range, connected, open-ended learning online, MOOCs are becoming something else altogether. Locked-down. DRM’d. Publisher and profit friendly. Offered via a closed portal, not via the open Web.”

This enclosure is about profit models, not learning. And it profits few, in the end, because – as I got het up about in Inside Higher Ed last week – the societal mythology of education as value really only functions if institutionalized credentials in some way tie to social mobility and lucrative work.

That’s not the game we’re in, anymore.

But here’s the thing: MOOCs are a symptom of change in higher ed, not the source of it. We need to find ways of talking about this enclosure of openness by profit models, without conflating these forces with online ed in general or even entirely with MOOCs.

Because we will not resist the corporatization of education by standing solely for conventional institutionalized models. That horse has left the barn. But in online practices there may still be ways to protect and preserve some of the broad societal concept of the “we” that institutions were intended to enshrine.

MOOCs as Symptom: Networks + Neoliberalism

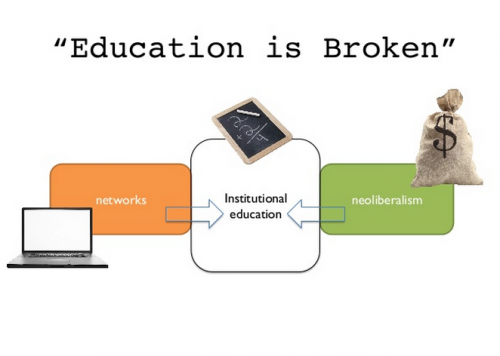

Basically, this is where we are: traditional institutional education is being encroached upon from all sides. And the big MOOCs conflate the two primary forces for change: networks and neoliberalism.

This is an ugly slide – I kinda like to call the clip art “retro” – but it’s the best illustration I have at the current moment for what I see actually happening to higher ed as we’ve known it. From one side, what George Siemens terms “the Internet happening to education,” or the networked opening of what was conventionally the closed domain of knowledge. From the other, the market incursion into the sphere of education, with its attendant ideological leanings towards the measurable and the profitable.

Last week, Dave & I went to two conferences together. We do the majority of our conference travel independently, so even getting to be at the same events was kind of exotic for us: being invited together was a treat. But blending our two separate strains of thought into a single keynote for the second conference was something we haven’t done in a couple of years, since all the MOOC stuff blew up.

We bickered about process: that’s par for the course, for us. We’ve worked together as long as we’ve known each other, and while our ideas and even perspectives tend to complement the other’s, our ways of getting there are pretty much opposite. (Sidenote: our writing on the MOOCbook has been pretty much two solitudes, enabling us to continue our lawyer-free relationship.)

But in the process of pulling together, between the two of us, three hour-long presentations to be delivered over the course of three days, on separate but intertwined topics, something converged and snapped into focus.

I’ve been looking at networks from an identities perspective for a few years now, trying to understand who we are when we’re online and what it is about this whole experience that actually matters, from an education perspective. Dave’s been wending his way through an exploration of rhizomatic learning as a way of navigating uncertainty within an era of knowledge abundance. Both of us have been thinking a lot about MOOCs and what they mean for change within higher ed. Hell, most of our household income comes from academic institutions, so the current budget crunch hits home.

But it became clear this week that our work needs to be about finding ways to use networks to push back against the neoliberal vision of the future of education. About making clear that the two do not share the same set of interests.

The conflation of the two is everywhere. Salon has an interview with Jaron Lanier today that makes the case that the Internet killed the middle class. Lanier’s arguments conflate networks with neoliberalism, making the latter invisible as a force unto itself. Sure, there are places where networked practices rely on neoliberal approaches to the world, in the sense of Foucault’s “entrepreneur of the self.” And neoliberalism often co-opts networked practices and naturalizes the perception that the two are one and the same.

But I don’t think they are. At least…I don’t think they inherently are.

Whether they become so is up to us. Particularly those of us who share the values espoused by public education. We need to build our learning and teaching networks, share our ideas and our questions and our practices and what works and doesn’t, and refuse to be enclosed.

Institutional concepts of educational practices enclose easily: that is their nature. The transition from institutional models of the classroom to a massive for-profit textbook magnate’s version of the classroom isn’t really much of a transition, except in what gets lost in terms of public values.

Networks don’t actually enclose easily. Hence the idea of “participate or perish” that Dave & I came up with the night before our keynote at #WILU2013 in Fredericton: a new academic imperative for our times.

Don’t just publish, because the institutional models are encroached upon and becoming enclosed. Participate. Make things different. Don’t wait for it to be your “job:” that’s institutional thinking. Institutional jobs won’t be there if we let the profit models gut education entirely.

Here are our slides from WILU2013, which trace some of these ideas through our own research lenses.

And here are the slides from my Spotlight Speaker session at CONNECT2013, where I focused in more detail on the participation and networking side of things: on how to go beyond institutional identities. Help yourself.

(Postscript: the “Education is Broken” Narrative as Sniff Test)

I want to return to this one in more depth…but a quick thought. The phrase “education is broken” gets thrown around a lot in the current educational climate. It is, in a sense, one of the key reasons neoliberalism and networks get conflated: it’s the area in which they agree.

But from one perspective, the idea that education is broken is a learning claim. From the other, it’s a credentialing and business model claim.

If you’re in the process of learning to tell the difference, don’t necessarily run from anything that claims education is broken. Rather, ask what aspect of ed it frames as broken. Is it the learning? You might be looking at a network. Is it the profit model and the structure and the means of offering credential? Probably neoliberalism and enclosure at work.

You’re welcome. ;)

Remember that wonderful book, The University in Ruins? The metaphor persists.

i hadn’t heard of it, Pamela…but looked it up and looks like i should read it.

published in 1997, huh? the idea that none of this is new but rather was visible 15-20 years ago, especially regarding the corporatism, bites. my own culpability in turning a blind eye, writ large.

I don’t have time for a full critique, but I would say your understanding of “market forces” is flawed. For-profit vs for-growth institutions do not differ in their response to market forces: they do their damnedest to control them. Pure “market forces” are the decisions of individual people, felt en masse. What happened to higher ed is basically a whole lot of people like you who made decisions within institutions that led to people – individual students, community members, parents of school children – being less able to make their own decisions.

The resulting discontent and feeling of being trapped led to a widespread push for change, which neither type of institution adapted to – the for-growth institutions least of all because it is more buffered. So governments took a short-cut, and enter the for-profit option. Sorry, but if you become a barrier, people will go around you.

For-profits are not the right answer, but the easy one – I’m not here to excuse governments for making that choice.

MOOCs are an expression of personal preference that the for-growth institutions (universities, school districts) have utterly failed to satisfy. If there were no internet today, this would be expressing itself some other way.

Neoliberalism is a fairy tale that people in institutions have told themselves to excuse their own lack of responsiveness. I’m afraid, if you are looking for an enemy, it has been yourself – allowing household income to become fully dependent on institutionally-imposed dictatorship over people’s lives.

Welcome to the world of uncertainty that most of your funders – taxpayers – live in. And the corresponding freedom :-)

Wow, that’s hostile. And points to the very problem at the core of the neoliberal rhetoric for education.

Karin, neoliberalism may be a touchy term, but it’s an overt economic and social paradigm, not a fairy tale. Your presentation of “market forces” as simply a collective of individual decisions, free of political agenda or underlying profit motive, is disingenuous. Neoliberalism is a political position just as my own preference for “public” solutions (though not actually institutional, as you’d see if were to look through the post/slides) is a political position. You’ve embodied neoliberalism nicely here, actually: far better than bickering over a Foucault vs. Chomsky vs. Thatcher interpretation.

We can disagree on politics. We can discuss what kind of values and solutions are a way forward for education – for instance, I agree with your points on MOOCs. I also think networks will continue to bleed beyond the enclosure of what I see as technosolutionism and for-profit solutions for education. I even think those networks might be far better options than institutionalized education as we’ve known it. But we’d probably have a far better conversation about all this if you read beyond your own apparent trigger words and didn’t caricature others’ positions, especially with “people like you” statements.

To be clear, I’m not actually “in an institution” in the sense that you appear hostile to. I haven’t been part of the decision-making process you refer to. I am long-networked, a freelancer and a grad student, lucky enough currently to have federal funding, but quite familiar with uncertainty, thank you. I also teach sessionally within my own faculty…or did, before the most recent budget cuts.

I am good at what I do, in the “Me Inc” sense where networks and neoliberalism overlap. But education is my field and my interest, so my income still comes largely from institutions, though on a contract basis. There is some freedom to that position, but be wary of over-romanticizing it: the precariat is a winner-take-all game.

And that conflicts with what I happen to believe education should be. Which is what this post is actually about – trying to find ways to keep some semblance of the values of public education and the idea that we have a society, not just a clot of individuals – alive, in spite of the failures of institutions and the direct undermining of them by positions like yours.

I love your posts. Forward, insightful.

It’s intriguing to sit back and say yeah but. As much as I enjoy possibilities, there are those realities that make you stop and think.

Apparently in Australian higher education the uptake of networked life is lower than expected. And in the bigger picture, a teeny-tiny portion of the population actually engages in the engaging-ways -of –online, we (whatever we are) have come to believe are so transformative. Reality is the overwhelming majority people consume the Web and now think in terms of consuming education.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjet.12060/full

I’m not surprised. Are you?

There are reasons then to resist and rebel, and to politicize not just what’s going on in higher education but as Lanier reminds us, the dismantling of a desirable livelihood with livable wages.

Thanks for the article link, Suzanne…timely, as I try to hone my thesis proposal today and struggle to put my finger on exactly what you’re pointing to. I suspect similar uptake might be seen here in North America. Increasingly, the possibilities of open networking appear to be perceived primarily as social, at least by the educators I encounter…which is part of the reason behind this overt push towards participation. Moving beyond consumption seem to me to be one of the few ways to avoid enclosure, but will not happen as long as participation continues to be seen as an add-on or trivialized as simply social behaviour. Making visible what we do and the value of it may be more necessary than we would have thought in the heyday of openness a few years back.

Openness is perceived of as social because most of the networks came to the attention of educators via student use of social media, and in some cases by eager colleagues applying that trend to their classes. The networks among professionals remain relatively the same as they were five years ago – networked educators talk to each other but those who aren’t in the web loop aren’t in the conversation. I have seen no massive increase in blogging or online discussion among educators, only an outpouring of weak “n=7” research that doesn’t seem to be helping anything except to get people with bizarre degrees employment as tools of institutions.

For many people, the web is a television with convenient ways to order consumer goods and keep in touch with friends and family. We need to create a paradigm where the eager sharing we see in hallway conversations on campus takes place online. Everyone has gotten hooked into long, involved conversations about pedagogy in hallways before, even more so than into conversations about family, which tend to be one-on-one. I frankly haven’t seen a good online space for that kind of activity.

So if I understand you right (I’m coming from a decidedly non-academic background, so perhaps I’m not!), you’re saying that in the last few decades, a lot of companies have figured out ways to make money off education, and we the public let them; and now those same (or similar) companies are figuring out how to make money from online education, esp. in the form of MOOCs. And one way to make money from online ed is to charge for entry (to ‘enclose’). So where you’d thought that moving education online decreased barriers to entry, it did not; and where you’d thought it encouraged open communication among disparate peoples — since disparate people could get in — it did not. Is that about right?

And some people say that these companies’ tendencies to enclose online education is the inherent fault of online education; but you argue that it’s a symptom of what’s happening to education as a whole. Yes?

Pingback: On Higher Education | Learner Weblog

Pingback: Week 3 by Dave Cormier – Forget the Learners, How do I Measure a MOOC Quality Experience for ME?! | MOOC Quality Project

Pingback: Speculative Diction | MOOCs, Access, and Privileged Assumptions | University Affairs

Pingback: MOOC Hype & Hesitance – Excerpts from MOOC Research | All MOOCs, All The Time