A couple of weeks back, I gave the closing keynote in Keene State College’s Open Education spring speaker series.

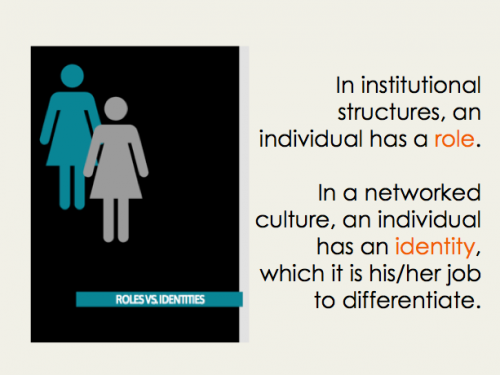

It was a rumination on Open as a set of practices and a site of identity, particularly for those of us in higher ed. I wanted to consider what it means to engage in digital scholarship – and digital leadership – from an identity perspective rather than a role perspective…especially for those of us for whom the standard higher ed roles and labels of student/staff/faculty may be only partial or precarious, aspirational rather than fully institutionalized.

Now, one of these days I will become one of those people who actually writes out their talks. Until that day, Dear Reader, all I have for you is Slideshare and my tendency to post talks as jumping-off points rather than transcriptions.

***

This particular slide deck is a REAL jumping off point, though. Because I was in the middle of my talk – mouth open, mid-sentence – when an awkward realization kinda opened up in front of me.

The connection I was trying to make between digital identity and digital citizenship in the open? Has a big gaping contradiction in it.

Nothing like a lightbulb moment in the middle of a narrative in front of a room full of people.

The point of my talk was that we need to go beyond thinking about identity in the open – digital identity – and start thinking in terms of digital citizenship.

Identities never generate in a vacuum; we are mockingbirds, mimics, ornery creatures whose Becoming is always relational, even if often in reaction to what we don’t want to be. Our digital identities are no different…and unfettered individualism, as a lens, tends to do a TERRIBLE job of acknowledging the ways collaboration and cooperation make the spaces in which we Become actually liveable.

So the presentation for Keene was about going beyond ideas of individual digital identity to ideas of digital citizenship and the shared commons…while acknowledging citizenship as a flawed framework that brings up issues of borders and empire and power. It was about the fact that we can’t really talk about digital identity without talking about citizenship, because when we’re all out in the open Becoming identities together, we’re shaping the space we all inhabit.

But. If I was right on this point – and I still think I was but hey, you can take that up in the comments – it was the other side of the argument that blindsided me.

I hadn’t fully – until that moment in front of the keynote audience – thought through how digital identity, as a practice, operates counter to the collaboration and cooperation that need to be part of digital citizenship.

This is our contemporary contradiction: identity as a construct in contemporary social media spaces makes for pretty rotten social spaces.

We know this. You know this. Much as many of us appreciate and enjoy aspects of the ambient sociality and community that social network platforms deliver us – shout out to everybody who hit “like” on the photos of the Hogwarts letter we made for my son’s eleventh birthday today, because those likes are, frankly, validating whereas if I parade the letter up and down my actual street I’m just weird – we all know there are fundamental drawbacks.

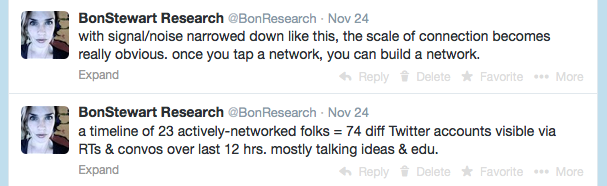

We’re algorithmically manipulated. We’re surveilled. We’re encouraged to speak rather than listen. We’re stuck engaging in visibility strategies, whether we admit it or not, in order simply to be acknowledged and seen within a social or professional space.

Our digital identities do not – and at the level of technological affordances and inherent structure, cannot – create a commons that is actually a healthy pro-social space.

And yet. And yet. Here we all are.

***

What I realized in developing the talk for Keene was that I used to write a lot about identity, and digital identities…and I stopped.

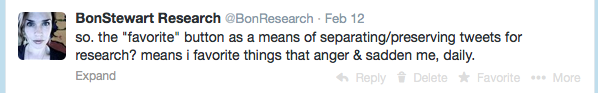

In the early days of this blog, digital identity was the crux of the phenomenon I was trying to work out and develop a research approach to: the why and the how of making ourselves visible and public in open, online spaces. In those early days, blog comments were still alive and well and many, many people contributed – generously, chorally – to my understanding of identity in the overlapping networked publics that blogging and academic Twitter comprised, back then. I’d been blogging in narrative communities for years, and had watched how monetization and scale of visibility shaped and shifted not only people’s presentation of self, but their experience of it, in the digital context.

I wrote about six key selves of digital identity. I wrote posts with David Bowie songs as titles. I played with messy ideas like brand and cyborgs and never did write as much about theory as I’d intended when I started out and gave the blog a name. But it was mostly identity that I focused on in those first few years.

And then I more or less walked away.

On the flights home from New Hampshire, I reflected on this; on the fact that even in my dissertation, I took up identity and digital identity but balked around focusing enough on it to theorize it, to fully unpack it. Because I knew it was the wrong lens for the socio-technical scholarly sphere I was trying to explore…but I didn’t know why.

Until I finally unravelled what bothered me about it, in the middle of a talk at Keene.

Digital identity isn’t just the wrong lens for figuring out digital scholarship, or encouraging participatory engagement in learning. It’s actually the wrong lens for building towards any vision of digital citizenship that makes for a liveable, decent digital social sphere to inhabit.

You probably already knew that. But I feel like something finally fell into place…years later than it ought to have, maybe, but nonetheless.

Now the question is how do we really get past identity and build for citizenship, in environments that limit, organize, and shape our sociality in ways we often even cannot see?