This is post #2 in a series outlining my ongoing dissertation research into how scholars using online networks build identity positions, reputations, and influence. The original call for participants for the research project is here, and the first post in the series is here.

***

In November of 2013, I created a new identity for myself.

I didn’t entirely realize it at the time. If you’d asked me, I’d have said – very carefully – that I was only creating a new Twitter profile. After years of digging into digital identities and writing a couple of rather long thesis proposals, the idea of conflating identities and profiles sounded like a cheap and sloppy business to me. And it is, frankly: the two are not the same.

But neither, I think, are they as different as I’d have claimed before I spent three months looking at the world through the eyes of my short-lived alter-ego, @BonResearch.

Becoming: Giving Account of an Account

I created the @BonResearch account as a lens for the participant observation portion of my dissertation study, a portal through which to observe and take notes on the networked practices of the 14 participants and 8 exemplar identities who agreed to be part of my research.

I opened the account on November 21st, 2013, and worked with it almost daily through February 25th, 2014.

I’ve been an active Twitter user, as @bonstewart, since 2007. On the surface, the new @BonResearch profile was simply a different window on a platform I’d been actively using for more than six years. I used my own name and photo in the account profile, as well as the explicit term “research:” I had indicated to participants that I’d be observing them via an account created specifically for the research process. A couple of them checked in by direct message (DM) when I followed them just to confirm that the account was indeed operated by me and was not a spam or catfish profile.

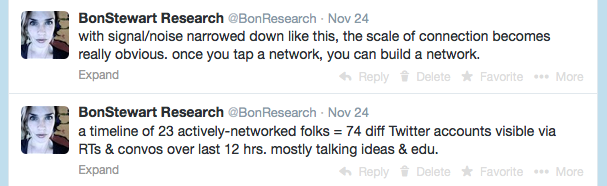

Because this account had a specific purpose, I was strict in keeping it focused on that purpose. I only followed the 22 participants and exemplars involved in the research, plus my own @bonstewart account: a tiny scale by most active Twitter standards. My inclusion of @bonstewart was both a nod to the autoethnographic aspect of this research project but also a means by which I could, if needed, use my primary account to retweet (RT) public points made by non-participants that I nonetheless wanted to flag for my research. I did this less than I’d anticipated: one aspect of Twitter that the @BonResearch lens made visible was the scale of RTs my participants circulated within their streams: following only 23 people meant that I noticed new or non-participant profiles in the @BonResearch feed, and there were many, as well as overlap in RTs among participants.

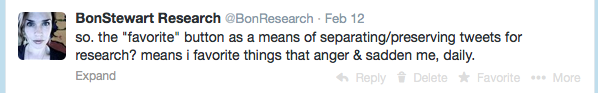

The majority of participants followed @BonResearch reciprocally, but not all. My thesis committee followed me, as did others in participants’ networks – often shortly after an action or communication that signalled @BonResearch’s existence to them. The primary observation tool I used to collect and organize data for my research was the ‘favorite’ feature, which I used to mark tweets I wanted to flag for analysis. Even had I kept the account mute and not tweeted my observations from it, this use of the ‘favorite’ button meant that it regularly signalled its presence to participants. It made itself visible in the world, and occasionally, through the favorite and RT processes, it drew attention outside the circle of my research. It circulated, in this sense, as an entity or identity on its own.

Of the 55 accounts that followed @BonResearch during the 3 months I actively used the account, at least 10 were unfamiliar to me and had no relationship to my @bonstewart identity. I engaged with and @replied to anyone who engaged with me, but communicated from it quite minimally: only 115 public tweets in the slightly-more-than-three-month span in which I used it, plus perhaps as many private Direct Messages (DMs), all with research participants. Thus @BonResearch was only perhaps a tenth as publicly prolific as @bonstewart during the same time period, but had far more extensive private communications with select individuals. These numbers are directly related to the specific goals of the account: I actively avoided drawing attention to @BonResearch, for fear that any scale of public scrutiny would limit my sense of the account being primarily for my own purposes.

This tension between signalling primarily to myself and signalling publicly was one of the key identity issues that the research process made visible. Everything felt *new* and slightly unfamiliar from the perspective of the second account: I had to grapple with questions of self-presentation and audience, and negotiate them publicly, on different terms than I was accustomed to inhabiting or embodying, as @bonstewart.

This took me by surprise, to an extent. It shouldn’t have: my dissertation explores how identity positions are constructed within academic networked publics. Its assumptions and questions are rooted in Haraway’s work: in the situated knowing, seeing, witnessing, and speaking that come from being located in particular positions at particular times. On some level I knew that each account would have to give an account of itself, in the process of narrating this research: it just hadn’t registered with me until I brought @BonResearch into being the full extent to which her account of the research process would differ from that of @bonstewart. This was in part because I initially thought of the new account in instrumental, not relational, terms.

Being: Accounting for Embodiment

When I designed the project, I was following nearly 1000 people with my @bonstewart account and anticipating teaching via Twitter during the course of the research. Trying to research 12 or 14 people out of 1000 struck me as a rotten signal/noise ratio, and from within the @bonstewart account, I knew I’d have no way to keep specific track of research data amidst the many other signals and communications that comprise my Twitter usage. For clarity of data and to maximize the platform’s observation potential, I decided I needed an account specifically for the project.

But what I didn’t grasp until the moment I sat down to tweet from the account was the way in which I’d need to come to terms with a sense of voice and parameters and identity in order to signal.

I knew this. My thesis proposal states overtly: “Networked practices can create new opportunities for public engagement with ideas (Weller, 2012), but they demand the construction, performance and curation of intelligible public identities as a price of admission” (Stewart, 2013, p. ). But until the moment I sat down to speak through the @BonResearch profile, I had forgotten how totalizing this is. I talk through the steps of writing oneself “into being” each time I present Twitter as a platform to educators, in classes and seminars, but I had forgotten how agonizing and uncertain it can be to sit in front of a screen with no sense of what your potential audience expect from you. I had forgotten how uncomfortable it is to engage publicly in overt identity work, from scratch.

The process has me grappling more deeply with the implications of Butler’s concept of performativity – particularly the part about citing norms that are intelligible – for the creation of identity positions in networks. It also has me grappling with the limits of the concept of embodiment, and wondering how embodiment needs to be reconceptualized for effective application to networked and participatory culture.

Haraway talks about situatedness as embodied, in the sense of being specifically located in time and space and societal structures. I am trying to think my way through the process of being ’embodied’ in a different profile, even while still being, y’know, encased in the same couch-ridden self as my other account. @BonResearch was a different instantiation of me, a distinct facet of self: her signals brought into being a specific – if intentionally limited and short-lived – digital identity.

And the process of coming to inhabit @BonResearch pointed out to me that it was distinctions in relational ties and identity positions and voice, rather than physical embodiment, that both distinguished my two accounts during the participant observation period, and connected them back to my broader sense of myself as a person connected to other people. I mused, at one point, about the cognitive dissonance of ‘favoriting’ participants’ tweets about topics as personal and painful as cancer and tenure denial and existential uncertainty about the future of higher education: these actions ran entirely counter to my usual practices as @bonstewart, and as a human being in any other social environment.

Yet because of the specific function and relational position of the @BonResearch account, I had to trust that the signals I sent were not misconstrued but understood as part of a specific role, a specific identity position. Had I engaged in the same actions from my @bonstewart account or in a different setting, I might have had to account for them very differently.

This research process, then, has, unintentionally, been a meta-investigation into how social media accounts cannot simply be used as research tools without giving accounts of themselves or the identity positions constructed through and by them. In my thesis proposal, I’d expressed my hope and intent to make this research process not just reflexive but what Haraway (1992) and Karen Barad (2007) call diffractive. Diffractive methodologies map where differences appear, with the aim of making a difference in the world. They record histories of interaction, interference, reinforcement and difference – with the intent of producing heterogeneous rather than homogeneous accounts. Recognizing the profiles through which I will account for this process as separate accounts, each with their own relational identity, is an important step for me in beginning to work from a diffractive methodological approach.

***

For all those of you who I engaged with as @BonResearch, does this resonate? Did you think of the account as in any way distinct from my @bonstewart profile, or from however you conceive of me as a person? How would you articulate those differences or distinctions? What commonalities did you also see or attribute to the accounts?

The way I saw the @BonResearch, it was an observer on digital identity and networked performance. So I felt that it was my duty to let it (you) execute the project itself and not intervene. Thus, when you favorited tweets, retweeted, engaged and otherwise interacted, I just let you look through those eyes. As weird as this sounds, as a researcher myself, I wanted to preserve the integrity of your research, so I let you favorite at will and not ask “why the hell are you favoriting my tweet!?”. I figured you were collecting data and engaging with it, and thus in time you’d let me know what you might have found there.

Hope this helps!

Pingback: Digital serendipity | raptnrent.me

I found the presence of @BonResearch strangely comforting, not so much a stalker as a curator and keeper of thoughts. This was valuable to me in precise ways because I’m currently undergoing quite challenging medical treatment, and am constantly reminded of the threat that this will affect my memory, in quite literal ways. So I would see @RonResearch come quietly up behind me with her star sticker system, and I felt like something was being kept safe. But I agree strongly with Raul that I felt the keeping was entirely at the gift of the project.

What I appreciated very much was the sense of collaboration this keeping practice made visible for me.

On the second question, of the “two-Bon” identity switching (terrible urge to make bonbon joke here), it made me aware that Twitter operates this way anyway. I follow people who switch identity within one account from time to time by changing name or profile pic; but more regularly I’m aware that users already, routinely, change tone for different functions. Some more than others.

I also follow people who have two accounts: a public account for semi-pro networking, and a kind of secret self. This seems like quite hard work to me.

Small side line thought: I have never used a picture of me in any of my online profiles. This originally was to do with being a bit anonymous, but because I chose a series of anonymous crowd faces from historical cinema audiences that really became for me part of a conversation about identity-within-spectacle that I’m having somewhat independently with myself — although it made D. Cormier think I was much sterner than I am!

Also, just noticed that by typing without glasses I have invented a third identity for you: @RonResearch. My gift to you! Use it sparingly.

giggle.

Not sure why I’m using my Twitter handle and not my name here. Oh well.

I didn’t really think anything of it, to be honest. I understood exactly why you were doing it, and was…amused at times when you “starred” things (really? you want to note THAT?).

But I’m sort of biased because I “know” you, and I guess as an academic, I have these different writerly identities myself. This was literally “Research Bonnie” who was writing a dissertation, so in the same way I go into my office to write, so to were you going into this Twitter profile to research. But, we’ve also talked to each other using that handle.

I KNEW IT WAS YOU ALL ALONG!

I was just happy to be involved and included.

What an interesting post, Bonnie – and thanks for the invitation to extend the conversation. Chiming in with Raul, Kate and Lee, I also found it both fascinating and strangely comforting to find you favouriting tweets now and then. You alerted me about your plans for the @bonresearch account when we spoke in January, so the way you used it (if not the issues it has raised) were clear to me. Like Lee, as a fellow researcher I was fascinated and intrigued by some of the particular “favourites”, but didn’t feel uncomfortable in any way.

As someone neck-deep in researching identity myself, I related to @bonresearch as just that — you with your researcher hat on. I’m fascinated with this aspect of negotiating identities. Decisions (and the occasional angst) about voice, signalling, identity and authenticity take place internally. Our decisions about how to tweet/speak, present and “be” in public spaces happen within ourselves. That momentary pause before clicking “Send Now”? Unseen. Those who receive our signals just read our tweets :) In your case, even though your two Twitter accounts had distinct purposes, I felt they were both authentically Bonnie. I felt your voice and values were consistent across the two accounts, even though you engaged in different activities with each.

I’m aware of these issues when asking students to use Twitter. It’s not the mechanics of tweeting which hold them back (though there is that), but decisions and dilemmas about voice, openness, privacy, and “trying on” new identities, e.g. scholarly as compared with social identities.

Rambling now, I think, so I’ll end this long comment!

But have to thank Kate for making me laugh out loud. @RonResearch — what a legend ;)

Pingback: On e-leadership and the future of our world: Move B*$ch Get out the way! - Phemie