I haven’t had much to say here lately about my, erm, thesis. I started this blog back in 2011 to try to work through the process in the open, but complexity and uncertainty and the MOOC book – which is still chugging along through various stages of labour – seem to have gotten the better of me over the past couple of semesters.

That, or I finally started listening to mother’s advice, in the “if you can’t say anything nice…” vein. The whole, “here, this is a dog’s breakfast! Please enjoy!” line seldom hooks a readership, unless they’re compulsive editors or have an excessive empathy drive. Or are procrastinating on their own writing (welcome!)

I did write an 80 page thesis proposal, as part of my comps portfolio last December. I passed (woot!), and became an official Ph.D candidate. But in the process it became clear that I’d bitten off about half the Internet as subject matter and wasn’t clear on how to focus the scale of the project to, um, do-able.

Do-able is, of course, the key to that magic future perfect (in the grammatic sense) state of “done.” So after much thinking and reading and talking with my advisors, I’ve skinned the scope and scale of the thesis down and am starting the proposal again. From scratch.

And I’m asking for input. Your eyes. Your suggestions. Your thoughts about potential participants. Your sympathies gin.

My introduction and “research problem” for the new proposal are below. What they begin to lay out will be an ethnography: a form of qualitative research that explores cultural phenomena and meanings and patterns from participants’ viewpoints, making visible what might otherwise be invisible to those outside the culture.

Or that’s the plan.

The culture under investigation here is one to which this blog is a (tiny) contributor: the public participatory sphere of scholarly networks. This subculture of the broader phenomenon of participatory culture spans Twitter and blogs and G+ and even major media spaces, but also runs parallel, in a sense, to institutional academia: the participants I study will all have a foot in both worlds, and the goal of the research is to make the operations and practices of the online sphere visible and intelligible to scholars (and the public) outside it. So I’m looking at digitally-networked practices and identities, as ever, but rather than beginning from a theoretical framework of the cyborg to which my data (ie participants) would need to conform, I’m starting instead from practice and experience.

Basically, I’m looking for and at academics and grad students and others all along the continuum of scholarship. I’m looking at the ways we build identities and reputations for our ideas outside of – but often in tandem with – accepted academic practices like publishing in refereed journals or climbing the tenure track ladder, particularly since that ladder has come to look a bit like Brigadoon for many within the ranks of adjuncts and graduate programs lately.

I’m drawing heavily here on the work of George Veletsianos and Royce Kimmons, who’ve been writing about Networked Participatory Scholarship (2011) for a couple of years now. I’m narrowing the focus of that concept by looking not just at the online participatory work of scholars, but specifically at the work of scholars for whom a significant portion of work and thinking and reputation-building occurs online. Using Dave White & Alison LeCornu’s (2011) visitors and residents model, I’m looking at resident online scholars, engaged in the kind of merged production/consumption Bruns (2008) calls produsage and Ritzer and Jurgenson (2010, with particular focus on unpaid labour in the context of abundance) term prosumption. In the intersection between residents, prosumption, and networked participatory scholarship, you have what I’m calling networked scholarly participation, or the subset of participatory culture that intersects with academia. I’m also drawing on the work Cristina Costa did in her recent dissertation on the participatory web’s relationship to academic research, though my study will focus less on research and more on reputation and identities development. the work of danah boyd and others on networked publics and the New London group’s literacies and new media literacies will frame my approach to what it means to work in public.

But there’s always more out there.

Being an open, networked teacher/learner/scholar means asking, “Hey, does this make sense? Is it silly? Is someone already doing it? How can I improve?” EVERY SINGLE TIME you put your work out there. It’s intimidating. I always forget, until that moment right before I hit “publish.”

But it also means getting answers to those questions while the work is still in progress, taking shape, and that is immensely helpful. So here goes. Take two on my thesis research problem, a draft, needing your eyes.

Does this make sense? Is it silly? Would you participate?

I’m all ears.

:)

Bon

Introduction:

Over the last decade, the ways in which people can to connect with one another and share ideas online have multiplied dramatically. Social network platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have become commonplace means of communication and interaction. The proliferation of free blogging platforms such as WordPress, Blogger, and Tumblr has enabled unprecedented self-publishing, and the rise of camera-enabled phones combined with platforms such as Youtube and Instagram has meant that images and videos can be freely shared as well. Participation in public conversations via the Internet has become a feature of contemporary life.

Many forms of online participation are becoming visible within contemporary academia, as well. Since the first computer-based courses in the 1980s (Mason 2005), learning management systems such as Blackboard and Moodle have been widely adopted by institutions in many countries, enabling both fully online and hybrid or blended courses, which combine face-to-face facilitation with supplemental online engagement. Pressure on institutions to deliver courses online has risen recently as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have become a buzzword across higher education: the New York Times went so far as to dub 2012 the ‘Year of the MOOC’ (Pappano, 2012).

The proliferation of online learning in higher education, however, goes far beyond the rise of online and hybrid classes and formal learning opportunities. The phenomenon of participatory culture (Jenkins, 2006) has begun to permeate higher education. Scholars themselves are going beyond teaching and searching online to building public bodies of work via participatory media; self-publishing, sharing ideas via multiple platforms, and engaging with emergent issues in higher education and society at large. Within this public, participatory intellectual sphere, networks of scholars and emerging scholars develop across multiple technological platforms, engaging with each other and each other’s work regularly. These networks of participation and collaboration may extend beyond online communications to face-to-face contacts if geographic limitations allow.

There are myriad platforms available for open scholarly networking, many with their own particular purpose. Social networking sites (SNS) such as Academia.edu have emerged specifically for scholars, while reference management tools such as Zotero and Mendeley have gradually integrated networking capacities for scholars to recommend, share, and tag resources. Twitter is a general but immensely adaptable platform: hashtags such as #highered, #cdnpse (Canadian post-secondary education), and #phdchat aggregate input from interested parties all over the world. Google hangouts are utilized to host informal open discussions and learning experiences, and Facebook groups focused around specific disciplinary and research interests enable real-time public discussion of issues and ideas. Nor are SNS the only means by which scholars connect and share their ideas: major media outlets and higher education news forums host blogs that amplify scholars’ opinions and voices; many academics share their own emerging ideas and observations via active independent blogs.

These networked practices not only connect scholars to each other across disciplinary lines; they open access to discussions that have traditionally occurred within more closed and formalized channels. Participatory scholarly networks therefore create new opportunities for public engagement with ideas (Weller, 2012) and can offer junior scholars and graduate students opportunities alternate channels for participation, leadership, and development of scholarly reputations. They can serve as communities of practice (Lave and Wenger, 1990) and informal learning communities for scholars, and foster what Lankshear and Knobel (2007) call “new literacies,” or an ethos of “mass participation, distributed expertise, valid and rewardable roles for all who pitch in” (p. 18).

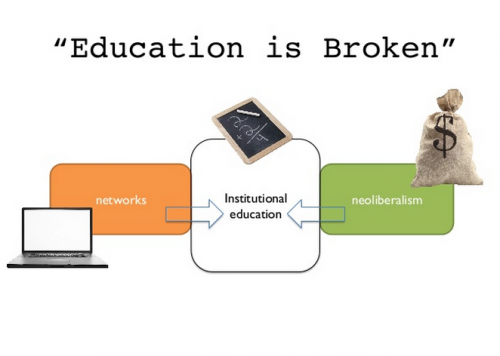

This ethos and practice of mass participation, however, does not align entirely with the institutionalized traditions and operations of academia. As Daniels (2013) notes, in her discussion of “legacy” (pre 21st century) model journalism and its implications for higher education, “We have our own “legacy” model of academic scholarship with distinct characteristics…analog, closed, removed from the public sphere, and monastic” (Legacy academic scholarship section, para. 3). While Daniels acknowledges that this legacy model is not necessarily as dominant or closed as it once was, she notes its retreat is partial and piecemeal (Legacy academic scholarship section, para. 2). There can be hesitation among academics about the risks involved in developing an online presence (King & Hargittai 2013) and sharing intellectual property. Some of the practices and identity roles cultivated via participation can appear transgressive or inconsequential when viewed through the lens of the academy.

The goal of this proposed dissertation research is to make visible how those same practices and identities appear when viewed through the lens of new literacies and mass participation. The work of Veletsianos (2011) and Veletsianos and Kimmons (2012, 2013) frames such practices as ‘networked participatory scholarship’ (Veletsianos, 2011). Defined as “scholars’ participation in online social networks to share, reflect upon, critique, improve, validate, and otherwise develop their scholarship,” (Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012), networked participatory scholarship is a framework that invites inquiry into the relationship between technology and scholarly practice, and into the techno-cultural pressures surrounding the use of digital technologies in academia. Networked participatory scholarship centres on individual scholars’ participatory engagement with digital technologies, and also on the effects of participation on scholarly practice. Its definition of scholar refers to any “individuals who participate in teaching and/or research endeavours (e.g., doctoral students, faculty members, instructors, and researchers)” (Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012, para. 2).

This proposed dissertation project will build on the concept of networked participatory scholarship in designing an ethnographic study of networked scholars, but will focus specifically on scholars whose networked participation is a central, sustained aspect of their scholarly work, identity, and reputation development. The study will therefore expand the literature on networked participatory scholarship while also narrowing the focus of the concept to a particular practice and group of practitioners as a subset of participatory culture. The project will re-frame this specific focus of study as networked scholarly participation.

In order to facilitate this re-framing, I intend to bring networked participatory scholarship into conversation with two other key frameworks related to online networked practices. The first of this is White and LeCornu’s (2011) visitors and residents typology for online engagement, which offers a means of framing participation and participatory buy-in beyond Prensky’s (2001) much-critiqued “digital natives” model; this study will focus, effectively, on what White and LeCornu call residents, or regular, active users. Second, the study will focus on scholars for whom networked participation involves ongoing production and sharing of ideas and resources related to their own scholarly inquiries. This demarcation is drawn from Bruns’ (2008) concept of a produsage economy, in which production and consumption are collapsed and combined via the interconnectedness of online networks and their capacity to create reciprocal audiences. Ritzer and Jurgenson’s (2010) notion of prosumption further contextualizes the combination of production and consumption into a prosumption model that takes into account societal trends towards abundance and unpaid labour.

Ultimately, then, the practices under investigation in this study will be those of scholars actively developing and sustaining a networked participatory identity and reputation while simultaneously engaged in institutional scholarly work.

Research Problem:

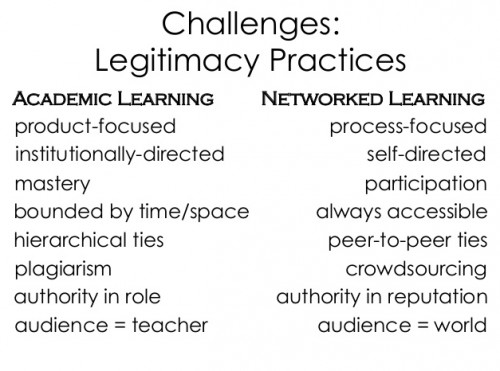

Both academia and social media can be said to be ‘reputational economies’ (Willinksy, 2010; Hearn, 2010), but the terms of entry and access for each are different, as are some of the values and practices upon which reputations are built.

For scholars active within participatory networks, this can mean navigating two sets of expectations, legitimacy standards, and concepts of success at the same time, as well as negotiating institutional relationships with peers, superiors, and students for whom the participatory set of terms may be invisible or devalued.

This dissertation project will focus on making the terms of credibility and reputational value within participatory scholarly networks visible. The study will investigate the ways in which online networks open up identity and reputation spaces that may not otherwise be available. It will trace both distinctions and commonalities in the ways institutions and networks foster identities and reputations, from the perspectives of scholars who actively straddle both worlds.

Online networked participation demands the construction, performance and curation of sustained, intelligible public identities. There is no formalized route or guide for this process, nor a clear distinguishing point between non-engagement and engagement in the process. Whether one is an outsider, an insider, or somewhere between cannot always be clearly identified, particularly from an external viewpoint. Networks tend to be distributed and fluid entities, wherein “membership is mostly unrestricted and participants may know some but not all members of the network” (Dron and Anderson, 2009, section 4.2, Amongst scholars, para. 6). Participants, therefore, self-select into the cumulative and ongoing realm of networked belonging and reputation-building.

Academic belonging, on the other hand, is more overtly restricted and codified: identity roles such as ‘graduate student,’ ‘associate professor,’ and ‘adjunct’ have widely-understood meanings and criteria for belonging. An academic reputation requires clear membership within the hierarchic institution of the academy, through the completion of an advanced degree and, usually, the securing of a tenure track position. Within the tenure model, success is incremental and reputation tied at least in part to clear externalized achievements:

Those who work within the academy become very skilled at judging

the stuff of reputations. Where has the person’s work been published,

what claims of priority in discovery have they established, how often

have they been cited, how and where reviewed, what prizes won,

what institutional ties earned, what organizations led?

(Willinsky, 2010, p. 297)

In both online and formal academic spheres, reputations are also dependent on relational ineffables such as social capital (Bourdieu, 1984), and the goodwill and esteem of peers. These and other commonalities will be included in the study. But the premise of this research is that the terms on which reputations are built, enhanced and taken up within the ethos of mass participation exemplified by scholarly online networks demand specific attention and articulation.

This dissertation proposal, then, proposes an ethnographic exploration of participatory scholarly networks. Its intent is to conduct a sustained ethnographic investigation into the ways scholarly practices and identities are shaped, enabled and constrained by online participatory networks. The study will investigate the ways in which scholars enact and experience scholarly engagement, research and research dissemination, and reputation-building within participatory online networks. It will attempt to make visible both overlaps and differences between these practices and those experienced within institutional contexts. Distinctions will be framed both in terms of the differing affordances of online and offline interactions and between what the literature frames as the differing mindsets (Barlow, 1995, in an interview with Tunbridge) or paradigms shaping physical space and cyberspace.

What do these participatory networks offer scholars? What – if anything – is their value and advantage over more conventional forms of scholarly networking, such as that which occurs at academic conferences and symposia? What do they offer over established forms of idea sharing and reputation development? What are their disadvantages? In what ways are they complementary? These questions will form the guiding core of this research investigation.