The Preamble:

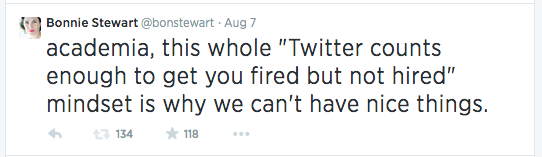

I am the sort of person who was born to be elderly and didactic. Deep in my nature lurks the spirit – if not the vocabulary – of a teeny, slightly melancholic sixth cousin of Marcel Proust hankering to wax pensively about the eternal nature of change and What Once Was. Inside my head, it’s all Remembrance of Things Past, all the time. Not because I’m nostalgic – je ne regrette rien! – but because this appears, even at midlife, to be my only wayfinding strategy; reflective recall is how I make sense of the world.

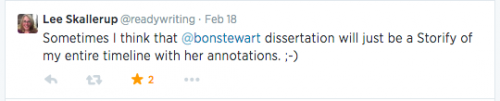

So I cannot leap back onto the blog after four months of TOTAL SILENCE without spitting up metaphors. I am surfacing from the thesis. I am almost at the finish. I am beginning to get my voice back; my feet back under me. You would be forgiven for thinking I’ve been engaged in some kind of strange swimming marathon. Or drowning. Because both are true in the ways that matter even through really I’ve barely left my couch in three months. Back about mid-November I embarked on the gradual withdrawal from everything except my thesis (and working and parenting and – sadly – shovelling SEVEN FEET of %#&*(ing snow). And it is done and submitted, which is still surreal to me. It is three papers and another forty-odd pages and has itself a fancy title and will be defended in April, warts and all. It is about scholarship in the context of knowledge abundance and how online networked practices intersect with/assemble with institutional practices in terms of influence and engagement and attention, in particular. It is basically a slice of a particular cross-section of academic Twitter circa early 2014. And it is done (I never really actually thought it would be done). Done.

The first paper of the three that comprise the body of the thesis was actually finished and submitted back in July, which feels like a misty past now, The Time Before. That paper came out today and the pre-print is here if, like me, you don’t actually have access. And below I am going to break it down into the Very Short Version in case reading 38 pages isn’t what you’re on about.

But this is The Preamble and elderly didactic cousin-of-Proust me just wants to chew upon how different it all was when all my words were being lined up tidily for academic digestion. I nearly choked getting them out. I nearly choked on having no time to think in This Voice, because I had to give up most of my tweeting and all of my blogging to get the thesis finished and yet in doing so I gave up my primary wayfinding and sensemaking processes and that felt exactly as untenable as you would imagine and it was all *almost* as ironic, to me, as the fact that my first paper for the thesis is about openness and networks in a closed journal. But you may as well laugh as cry, right? I made each of these irreconcilable choices. These are the contradictions of our time and even researching them has not helped me navigate them remotely cleanly or well. I do not know what all this means for my future in whatever academia is becoming but I do know that writing in my own voice gives me joy and not writing in my own voice breaks my spirit and I do not think I want to slide so far away from the networked side of things again for awhile yet. And still.

Je ne regrette rien.

The Paper, SHORT VERSION:

This paper is about what counts as academic influence on a platform like Twitter.

Influence is how we determine the reputation and credibility and essentially the status of a scholar. There are two ways we assess influence: first, there’s the teeny little group of people who understand what your work really means. Then there’s everybody else, from different fields, who piece together the picture from external signals: what journals you publish in, what school you went to, your citation count, your h-index, your last grant. Things people recognize and trust. It’s a complicated shorthand.

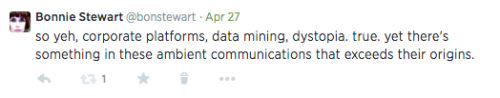

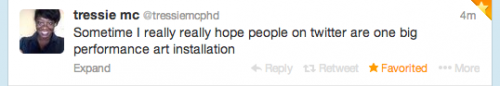

And now, in the mix – against a backdrop of knowledge abundance and digital technologies and the fact that nobody needs to go through a gatekeeping institution to contribute to knowledge anymore – Twitter. This paper explores what circulates or counts as influence and credibility in academic Twitter, and in networked participatory scholarship more broadly.

The paper concludes that scholars assess the networked profiles and behaviours of peers through a logic of influence that is – at least as yet – less codified and numeric than expected. Participants in the study did perceive relatively large-scale accounts as a general signal of influence, but recognizability and commonality are as or more important than quantifiable measures or credentials.

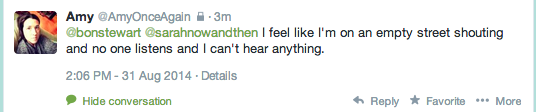

The paper suggests that the impression of capacity for meaningful contribution is key to cultivating influence and the regard of actively networked peers. The value and meaning of that sense of contribution is tied in part to the ways in which network signals operate individual to individual – more on that in papers #2 and #3 of the thesis, as well as its conclusion. The value is also, frankly, in the fact that we can see our signals received, in networks, in real-time. Never underestimate the power of people listening.

Key messages from the findings of the paper:

1. Metrics matter, but not that much

2. Scale of visibility (ie having a large account and a large active reach) is a signal of influence but also a weird and complex identity space

3. The intersection of high network status with lower or unclear institutional academic status is also a weird and complex identity space

4. The perception of someone’s capacity for contribution is created and amplified by common interests, disciplines, and shared ties/peers

5. Institutional affiliations aren’t considered that important by active Twitter users (unless they’re Oxford)

6. Automated signals indicate low influence

7. Digital networks offer scholars a sense of being someone who can contribute…in ways that the academy does not offer. (The academy offers other ways. But this paper focuses on the signals and lived experiences of networks.)

If you want to read the rest, there’s lots. The official article is here, and the open pre-print is here. Your feedback and your thoughts and your ideas are very welcome. :)

The Post-script:

The fourteen participants and eight examplars who stepped forward to be a part of this research…I thank all of you hugely, for your time, and your teaching, and mostly for your trust.