In a little less than two weeks time, I’m facilitating a week-long discussion/overview/ exploration on “Building a Networked Identity: Becoming a Connected Educator” as part of the #wweopen13 MOOC-ish course on Online Instruction for Open Educators.

I say MOOC-ish because the term has become so fraught lately I’m not even sure what people conjure up when they hear it. Insidious corporate encroachment and consolidation of Big Ed interests? Yep, that’s definitely under the big MOOC tent. Something interesting to do? That’s there too. A learning structure not entirely given over to the logics and informatics of domination? Depends entirely on the model.

(Note: there is a difference between what MOOCs in their many incarnations actually bring to the education conversation and what they’re sold as bringing. A revolutionary solution for educating society? Please, no. That’s just PR and the fantasy of free market education, not something any MOOC has any business claiming. Even if they insist on claiming it. There are things MOOCs are good for, and then there’s the hype cycle. Caveat emptor.)

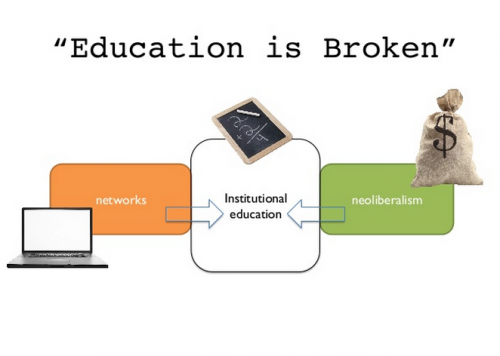

Anyhoo. Like George Veletsianos says in his slides from last week’s COHERE 2013 conference, MOOCs represent something broader than any of the courses – or even the platforms – themselves: they’re a phenomenon, a symptom of the many chronic issues and narratives intersecting in education at this juncture. Enter #wweopen13, which ironically isn’t quite as open as it might like to be, bound as it is to a D2L LMS platform for this iteration. I’m trying to mitigate some of that platform constraint by doing my thinking aloud for the course here, before my week gets started. Because in a sense, I think the conversation about becoming a networked educator needs to be – at least in part – a truly public conversation, one where random connections can be made and the scope and scale of the discussion isn’t limited by membership on a class list, even if that class list is free to sign up for.

Which doesn’t mean I don’t want you to sign up: we’d LOVE to have you, even if only for the one week. Or all four remaining…it’s never too late. This week, Jenni Hayman & Sean Gallagher take you on a Tour of Technology. Next week, that Dave Cormier guy is going to go on about Community and Curriculum. It’ll be jolly. And any ideas and experiences you share here will effectively become part of the course conversation for the week I’m teaching, whether you make the leap into the course itself or no.

***

Connected Educator = An Identity

You’ll notice I’m talking about conversations. If you landed here hoping for a tidy list of failsafe takeaways for how to become a connected educator, mine’s disappointingly short. It goes something like this:

Step #1: um, talk to people. Online, offline…network with people who are interesting and interested in stuff you find interesting. Learn. Grow.

That’s it.

The whole week is designed around two things: the first is a meta-exploration of networked identities, or the implications of being a connected educator, especially in the online context. We’ll talk about different aspects of digital identities, and about how digitally-networked identities differ in structure and possibility from institutional identities. The second thing we’ll do is try to put some of those explorations into practice, with activities focused on your own profiles and networks.

*If* you want to. It’s a MOOC. There’s no grade, participation is voluntary, and you have the agency to decide what you want to do, and what you don’t. You may already be doing most of it, or connecting just fine offline and that’s enough for you, thankyouverymuch, and that’s all good by me. A vein of almost-evangelism about online connectedness has popped up, especially in the K-12 ed circuit, where people are sometimes made to feel as if they *have* to network online in order to be an effective, active, growing educator, and I don’t entirely believe that. I do think online connectedness can offer real value, and part of my focus during the #wweopen13 week will be on what that value is and how it differs from being connected offline. But you can take big or small or zero steps in that direction during our week: up to you. Just being part of the conversation – even about why you don’t want to network online in a professional capacity – is welcome.

How Networks Change Online Education

Because in a course on open online teaching, it’s important for me to emphasize that the open, networked side of online practice is different from just teaching via computer: networked activities can affect the pedagogy and power structures of your classes.

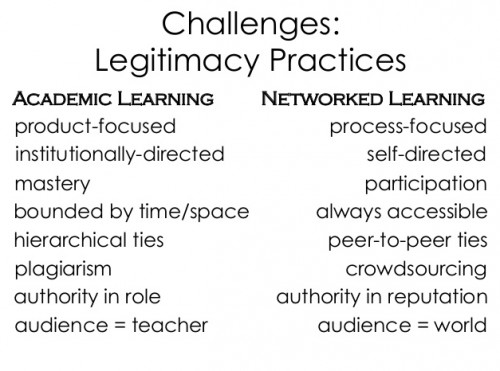

As Stephen Downes has been saying for years, there are key differences between groups and networks, and one is that groups are collections based on some property or commonality (welcome to kindergarten, all children born in 20o8!) whereas a network is an association. In associations, connections are more voluntary, but they also require visible signalling in order to occur. In a classroom, you can sit quietly all year and to some extent, you are nonetheless part of the group: visible, even if by your non-participation. In online networks in particular, non-participation does not signal. You need to make yourself visible in order to form connections; to become part of the association.

I research networked practices, or the ways people signal their participation. My work in online ed wasn’t always networked, though: I started in this field back in the early days, from 1998-2000, and have taught online and blended courses in a variety of higher ed settings since 2002. I’ve worked with and on platforms like Jones that don’t exist anymore, and on WebCT, Blackboard, Moodle, Canvas, and now D2L. I think a lot of valuable education can occur within the bounds of an LMS, just as it can occur within the bounds of a classroom…and both classroom and LMS spaces can provide what some learners experience as a safer, more supportive jumping-off point for learning than the cacophony and exposure of public conversation.

But. Habits and roles around education are learned early and deeply, and the line between safety and learned passivity can be hard to challenge, particularly in an online environment. The design and affordances of most LMS spaces parse conversation into discrete, digestible chunks that are teacher-controlled and linear, encouraging behaviours and practices that replicate traditional transmission-style education, or what Freire called the banking model. Even – and this is important – if that’s no one’s intent.

So if your vision of education is one of higher order thinking and open-ended inquiry and participatory networked connections, working entirely within a closed LMS isn’t necessarily optimal.

Which is where networks can certainly help. Networked learning means not just opening up the walls of the classroom to enable connection with those outside – Twitter discussions with authors being read, for example, or public posting of questions for input from students and whoever else is interested – but also reconfiguring the idea and power relations of the classroom itself. As George Siemens points out in this slideshow, the architecture of networked information is distributed, scalable, self-organizing and adaptive: it has no centre. So networked courses create temporary centres around it, but also leave the possibility of multiple rabbit holes and open-ended inquiries and meaningful connections open, ideally. More importantly, when the networking takes place using platforms participants already use in their daily lives, you create the opportunity for ongoing connection and learning long after the temporary centre of the course is finished.

Still, networked learning is messy. It requires a great deal of leadership and support from teachers/facilitators. It requires UNlearning, for teachers and students. And that unlearning has to take place at the identity level.

Networked Identities Begin with Unlearning

Participating in a networked learning environment involves confronting and smacking down ten or twenty years of implicit and internalized messages that tend to run a bit like this: Raise your hand, Bonnie. Stay on task, Bonnie. That book in your lap is NOT your math assignment, Bonnie. Please stop talking to your neighbour, Bonnie. Speak when you’re spoken to, Bonnie.

Image from https://dx5y3z85enc4t.cloudfront.net/540×540/fit/hostedimages/1380336007/694597.jpg

Ahem.

Now, those are not the only identity messages education teaches, at least if we’re lucky. I’ve had a great many wonderful teachers who’ve connected with me, been patient with me, altered my trajectories and fostered my gifts. But education is a system and tacitly, it systematizes us, even if it manages to exhort us to more. And when we hit networked learning environments, especially if they’re massive and open, those systematized identities can be an albatross.

Because in a networked environment, the contained one-to-many teacher-student relationship and responsibility which is the driving logic behind most of those systematizing practices (that, and the traditional role of teacher as knower) no longer operates. There’s no sense of where belonging to a given conversation begins and ends. For those of us who’ve internalized the “speak only when you’re called upon” message, the slow, painful, eventual realization is this: there is no one standing at the proverbial front of the class to validate our inner Lisa Simpson when she politely waves her hand. Waiting quietly to join in does not signal.

Likewise, from a teaching perspective, assuming everyone can and will just leap in and join the conversation doesn’t help foster any kind of real opportunities for participation for those who might struggle. We are all different, and some of us are used to being heard more than others. The old adage says “on the Internet nobody knows you’re a dog,” but that’s perhaps only because there’s no way to see who sits on cue. Our gendered, raced, classed embodied selves – who all fall along varying spectra of sexual orientation and gender performance and neurotypicality and ability AND whose ways of signalling identity and reading signals in conversation come from the experiences we’ve been accustomed to having in those respective bodies – shape the kinds of signalling and participating we’re comfortable doing. So…online is not the great leveller. Power relations manifest differently, but they’re still there. And thus teaching as a connected educator not only involves trying to create opportunities for people to participate or signal that they want to participate, but also being aware of power imbalances, modelling attentiveness, and trying to find backchannel ways of helping people feel as included as possible. Especially if conversation is your goal.

***

As a sort of trailer for my upcoming week with #wweopen13, I’d like to end this intro to networked identities in educational spaces by asking you – whether you’re in the course or wouldn’t be caught dead there, whether you have an online network of 3 or 30,000 – what YOUR experiences have been with networks, in or out of education, good or bad.

What are your stories? What are the risks? The joys? The things you think people should consider before embarking on this path of opening up the walls surrounding teacher & student identities?

And if you’re in the course or *thinking* of being a part of it…don’t worry. There won’t be any other invitations to do homework in advance. ;)